Last week: Stephen Crane, The Red Badge of Courage (1895)

This week: Jesmyn Ward, Salvage the Bones (2011)

Next week: no newsletter April 7th

Yesterday, over drinks, some colleagues and I talked about evacuations. No one else at the table had experienced one. One colleague had lived in New Orleans for two years pre-Katrina without a car, and though he had been invited by friends to join them on their journeys, his family chose not to. He remembered that it was watching his neighbors board up their homes and leave, that he started to get second thoughts, and that he felt lucky it veered west. “Magical place, New Orleans,” he said, smiling.

We evacuated from our home in New Orleans, many, many times. I believe the count from the period 2014-2021 was 8 evacuations, but it could be that I have miscounted. They tend to run together — distinguishable only by the cars we drove, and whether or not there was air-conditioning, and how severe the storm became. I was always in favor of evacuating. I had someplace to go that I loved to visit — my mom’s house is in the Northern part of the state — and I dislike high wind and driving in high water. I have troubling memories of earlier storms, and we have all cleaned up after too many floods. The next to last hurricane evacuation, for Barry (I think?) was precipitated by a reminder on the radio from the mayor’s office to “put a hatchet in your attic” in case the Mississippi River overtopped the levees. We left an hour later. I am not down for “hatchet-in-the-attic” weather.

There are stages to this: the first word of a storm starts to rumble into your conversations. Dad calls and tells you about it. A day passes, and it is hot and sunny and at the end of your to-do list. Then the conversations become exclusively about the storm, and your plans. Lots of people choose to stay, lots of people choose to go, lots of people flipflop. Plans are shared, spare beds offered, conversations get to be circular and indecisive and exclusively about the storm. “Might come see you this weekend Momma.” You stop buying one kind of groceries and start making another, the kind that doesn't need cooking or refrigeration. While you’re at the Rouses, you stop by the Fly to watch the River flow against the current with the storm surge, or you visit the lakefront out in Gentilly to see the big waves come in. Lots of baking, grilling, eating, drinking, boiling, and frying at this point, as we try to cook up the freezer. We start listening to the news, following the storm on twitter, checking in to see what Margaret Orr says. Schools and businesses close to “give families time for hurricane preparation” which I always translated to GTFO. Our last house had storm shutters that come down in “armadillo mode.” Friends start leaving, one an hour, sending back word about traffic — how many hours to Atlanta? how many hours to Jackson? — and you panic about topping off the gas tank. I always got cash too, in case we decided for some reason not to leave, and checked my go bag, stuffing in a few treasured things, photos and birth certificates mostly. The things I chose to bring changed each time. Park the electric car on high ground. Locate the blue tarps. Pick up the yard. Maybe the storm veers off the spaghetti model, or drops into a lower category, and you start to flirt with staying. You are filling up everything on site (bathtubs, empty bottles) with water, and making sure to stash some extra jugs in the attic. You are fastidious about charging your phone. Visit the neighbors for a headcount of who’s staying. And yes, you check to make the sure the hatchet is in the attic. Then the anxiety builds up, or maybe the contraflow gets opened on the highway, and you text everyone you know about the traffic, and off you go.

I’m sure your family’s evacuation plans looked differently — if so, tell us your sequence in the comments? — but I would say that our experience was somewhat typical for a middle class family in New Orleans. We had gas money, a place to go, a working vehicle, and a big community of support.

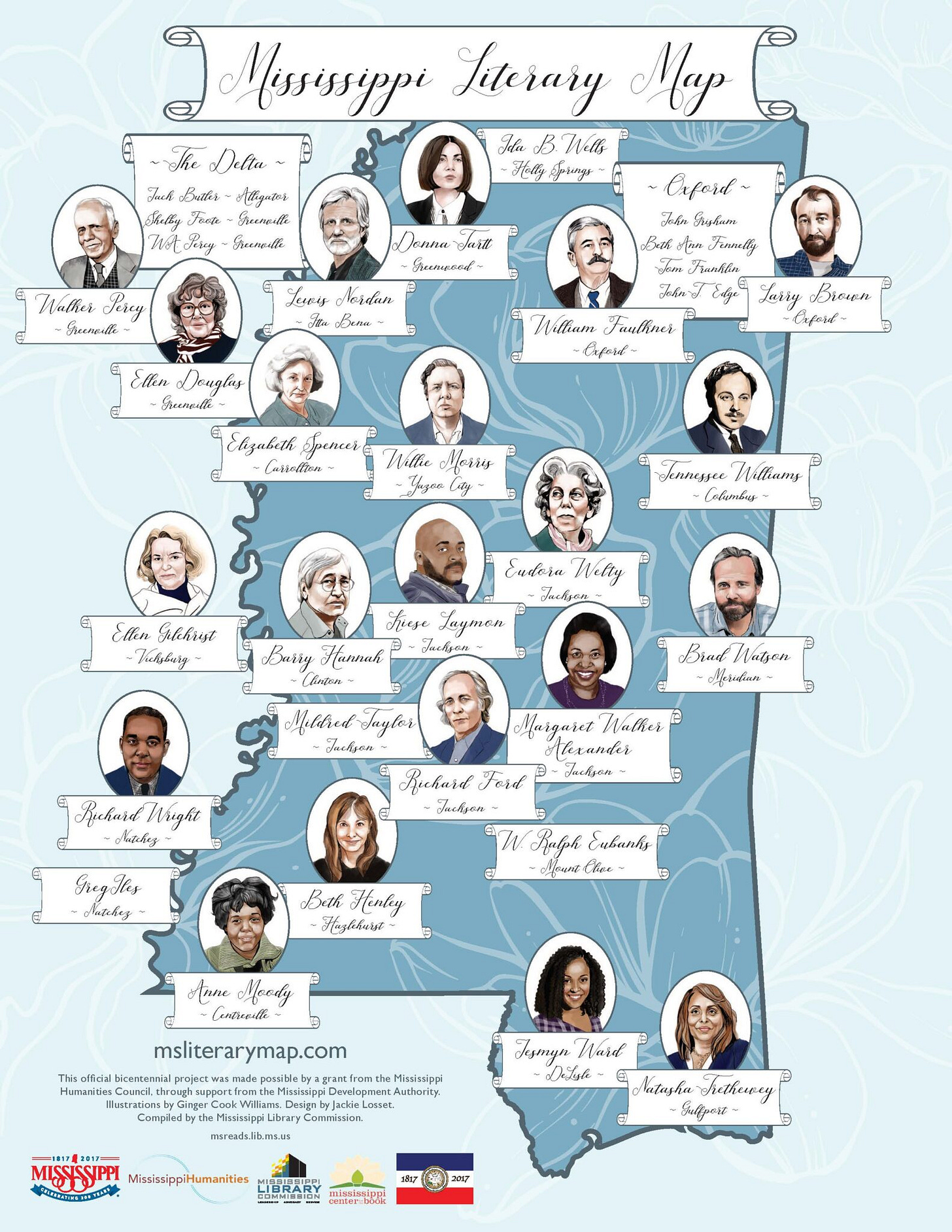

Jesmyn Ward (b. April 1977, same as me!) knows a thing or two about hurricanes. Her second novel, Savage the Bones (2011) is set in the fictional town of Bois Sauvage, Mississippi, a place based on her hometown of DeLisle. Mississippi, north of Pass Christian, and in the direct path of Hurricane Katrina in late August 2005. The book starts on that first word of a storm in the Gulf, “The First Day” and ends, 12 days later on the day after the storm “The Twelfth Day: Alive.” The paperback edition of the novel includes a final page that reproduces Ward’s interview with NPR’s All Things Considered, on her Katrina Story:

The water rose so quickly, we were afraid to climb into the attic. The stories of those who swam like my father, entire families who drowned in attics, terrified us. We did what we could to survive; we went out into the storm, wading through water chest deep, children clinging to our shoulders, and swam and scrambled for higher ground. (November 17, 2011)

So far, this is the most recent book to be featured on this newsletter. Three of her books won the National Book Award, and she’s now the youngest person to receive the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction. I am always surprised to learn, once I leave the Gulf South, how few of y’all have read her work. It may be because she largely writes about Black Rural Mississippi, and so gets pigeonholed as a regionalist. She has said she is deeply ambivalent about her hometown, where Black families are "pinioned beneath poverty and history and racism.” She said in an interview with the Paris Review that her stories have to be told with “narrative ruthlessness”:

I realized that if I was going to assume the responsibility of writing about my home, I needed narrative ruthlessness. I couldn’t dull the edges and fall in love with my characters and spare them. Life does not spare us.

She has said that this place gives her a sense of belonging, because “There's this entire web of people that I'm connected with, and I think that gives me a sense of myself that is hard for me to access when I'm not here. A way of understanding myself: who I am, and where I come from, and who I come from.” Of the 1500 or so people in DeLisle, Mississippi, Ward says that about 200 of them are her relations. Her novels and essays about this place and the people are ruthless masterpieces. She gets compared to Faulkner a lot in the criticism, but she’s cut a whole new path through the pines.

The narrator of Salvage the Bones is Esch Batiste, a fifteen-year-old girl with three brothers, living in “The Pit,” an intergenerational family compound on the outskirts of town. Her dad starts preparation for the storm on the First Day. As we learn in the first few pages, Esch’s mother died in childbirth, but she lives on in flashbacks that break open every third or fourth page. Esch and her brothers mostly raise each other, accompanied by a group of guys that hang around with her oldest brother, Randall, and a pit bull named China who accompanies her brother Skeetah. Esch learns on the second day that she is pregnant with the child of Manny, a golden Apollo boy, who clearly has no intention of claiming fatherhood.

The love and regard the four Batiste children hold for one another is breathtaking and whole and beautiful. They are enough.

But they have next to nothing, and their lives are precarious long before the storm. My students and I read this for our master’s level seminar on American Climate Fiction. I included it because it has these factors of interest to the genre:

the protagonist/narrator, Esch does not distinguish between culture/nature// animal/ human, and she has a striking awareness of the natural world around her that is seductive and sustainable and borderless

it is set in the recent past, rather than a speculative future. Climate change is now, the storms are getting worse, and they impact the poor in terrible ways, already, now people

the children live in a space of recycling, resilience, hunter/gatherer making do before and after the storm, and they are largely self-sufficient, positioned as they are outside or post-capitalism, all qualities that Climate Fiction foregrounds.

The book makes a statement about precocity, poverty, and resilience without saying it straight out. That is because the narrator, Esch, is bound by her own experiences which are limited. She doesn’t actually know what she doesn't know. Every now and then she notices lack — for example, at the grocery

“All the checkout lines are long. All the steel baskets are full. . . I feel I should have a basket, wonder if when these people look at us, they wonder where our supplies are. The cabinets at home have enough food to get us through a few days until the stores are back up and running, and if the cabinet’s don’t, Daddy will make sure to stock them if a storm hits. But the way the cashier’s apron hangs off one shoulder, like she hasn't had the time to pull it up with all the groceries she’s been scanning, makes me nervous.” (30)

So, in class, we took a few moments to talk about those areas in which Esch and her brothers are disadvantaged by poverty or poor governance: they do not have/do not access:

reproductive healthcare, medicine, clean bandages, fresh produce, enough food, mental health care or grief counseling, a working vehicle, college and educational opportunity, veterinary care, cable television, steady employment, public transportation, and evacuation support.

Evacuation isn’t mentioned in the book as a viable option. There is only this:

“Before a hurricane, the animals that can, leave. Birds fly north out of the storm, and everything else roams as far away from the winds and rain as possible. The air has been clear these past couple of days. Bright, every day almost unbearably bright and hot and close, the way that I feel when Manny is sweating over me: golden, burning. Insects root under our feet, squirrels leap from tree to tree, crows glide between the tops of the pines, cawing. The beat of their wings sounds soft as the swish of Mudda Ma’am’s broom when she sweeps the pine needles from her sandy front yard. Skeetah watches them the way he watches China: like any second she might speak, and he’s sure when it will happen, she will reveal all the answers to all the things he has ever wondered about. Daddy’s crazy, I think, obsessed with hurricanes this summer. He was convinced last summer after one tornado touched down at a shopping complex in Germaine that the Gulf Coast would be a new tornado alley. He spent the entire summer pointing out the safest places in the house to crouch. Every time he caught Junior in the kitchen, he made him practice the tornado drill we were all taught in school; kneel, fold over your thighs, tuck your head between your knees, cover your neck with your bony fingers to protect the soft throat underneath.” (45)

Esch has one book with her — the summer reading, Edith Hamilton’s Mythology (1942)— and with it Esch suffuses her world with the power of myth. She is Medea and her brother Skeetah is Jason. The dog China is also Medea, savage and loyal.

She also reads the natural world around her, watching it for clues and portent. Metaphors that center the natural world and/or explain human behavior ring through every paragraph. This aspect of the book makes it so powerfully vivid. How can the book be about precarity and deprivation and still be so abundant?

“The wind moves a little in the tops of the trees, and then dies away, like a person leaving the room. The trees are silent with longing.”

Skeetah shoots a squirrel and cooks it:

“The meat is stringy and hard, tastes half of red spice from the hot sauce, which has turned the bread pink, and half wild animal. I bite and I am eating acorns and leaping with feat to the small dark holes in the heart of old oak trees. The sun had set while Skeetah and I were looking for wood for the grill; the sky burst to color above us, and then the sun sank through the trees so that the color ran out of the sky like water out of a drain and left the sky bleached white to navy to dark.”

I could go on all day. You would think that with all this muddy description there wouldn’t be much time left over for characterization or plot or love, but you’d be wrong.

Hey everyone! This post is lucky #13! So I thought it would be fun to start setting them apart by number. How long will I go on? How long can I go on? Who knows! I figure when I run out of books, I’ll write about photographs again. Or maybe we can bring in some guests. Either way, I am so glad you are here, reading along with me.

Next week we’re taking off for a weekend with family and I will be back the following week with #14.

Enjoyed this post…. Remembering all the hurricanes!! And my own anxiety knowing you or Andy could be in the path! One year you stayed thru a hurricane in a house over 100 yr old! Empty streets, national guard… and I don’t think that tape on the windows ever came off! Andy took the train home one year, then had his car to head home ahead of Katrina, bringing along 4 very surprised kids from the southwest! We always enjoyed being the evacuation plan, especially with your ‘bubble family’ friends!