Among the ancients there were two worlds in existence

"The Iroquois Creation Story" as recorded in 1827

Last week:

This week: All over space/time, and the Iroquois Creation Story, as recorded in 1827 by David Cusack

We started a new school term last week, and with it came what my friend calls “syllabus season” or the period in which we try to make sense of all that we know and love in our field into one cohesive timeline, tidily organized into 13 weekly sessions of 2 hours each. So much gets left out.

A few years ago, my friend Kit Nichols with William Germano published a book about syllabi, Syllabus: The Remarkable, Unremarkable Document That Changes Everything (Princeton UP 2020). In it I found this handy disclaimer, which now appears on the slide for my first lecture:

A syllabus must make rules about epistemic practice: This is the evidence we will consider. This is how we will consider it. These are the ground rules for how we will work collectively through it.

Writing the syllabus is in itself an epistemic practice. Before writing the ground rules of engagement, we have to think about thinking. What thinking experiences do I hope students will take from our time together? In the last few years I have settled on this aim: “our goal is a critical familiarity with texts that have claimed a place in American literary history.” I’d also like to send them off with some textual analysis tools and soft skills and working definitions and situational context, but at the end of the day, my true aim is to open a window for metacognitive thinking about ideas, as expressed by this handful of people who happened to be born on the same land mass.

As you probably can already tell, I am not a fan of grading.

In this field, there are texts that are assumed to have an incontrovertible place on the reading list, and “new” texts that are presumed to be edging those stalwarts out. They don’t call it the “canon wars” for nothing. This seemingly esoteric “head of a pin”academic debate around reading lists will decide what evidence we will consider. It will guide who and what we talk about, and in turn, lead a new generation of students to assume they know what “American literature” is all about when they pass the class and move on to the next thing on their curriculum.

It’s not just this guy who cares about student reading lists. Banning books is an American tradition. Bringing them back on the list is our job.

In part, this is what makes American literature so fascinating to me as a field. VARIABILITY. No two syllabi are the same. With each new edition of the Norton Anthology of American Literature, new authors and texts are added, expanded, re-translated. We’ve rewritten the reading list entirely since I was a student, and I assume more changes are to come. I don't know this for sure, but I feel like there is more stability in other, older national canons.

One of the big questions on the table is: Where do we begin? When does “American literature” begin?

For many generations the answer to that question was 1620, the year that the Pilgrims departed from Leiden (whoop!) to pick up friends in England in ye old Mayflower and settle on the site of the Wampanoag village of Patuxet, which they called Plimoth. This story tracks with a traditional American literature canon, as it highlights a literate community whose writings and mindset would influence a whole host of canonical American writers living in Massachusetts, namely Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Louisa May Alcott, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Emily Dickinson…to name a few. The Pilgrims/Puritans brought with them a literary culture that hewed closely to the English literary tradition, and they kept detailed records of introspection that were, conveniently, written down and well archived. This is the school house rock version of our origin story, complete with the myths of religious liberty, Thanksgiving, American exceptionalism, and witches.

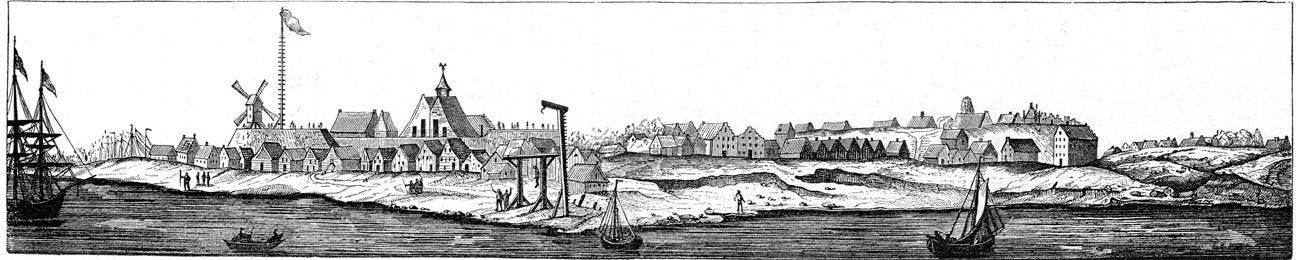

Another group of texts emerges if we start in 1609, which is the founding of New Amsterdam in the place known as Manhattoes. If we focus our attention on New Amsterdam (waarom niet?) more of the cultural diversity of the Atlantic world emerges: early New York had 11 official languages spoken; the charter they won permitted free movement of goods and free people in and out of the colony; and unlike in Boston, this free movement brought new ideas, tastes, and books. Starting with the Dutch promotes another set of canonical authors we can consider later in the semester from this context: Washington Irving, Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, Sojourner Truth.

It wasn’t until around 1993 that Spanish colonial works were included in American literary anthologies, although they tell the stories of most of the Caribbean, the Gulf South and South West. Approximately 41 million Americans (15%) are native Spanish speakers, but this is a class that is usually taught in English. Which begs the question, why is this an English class? At that time there were 400 languages in North America, 11 recognized dialects in New Amsterdam, 6 recognized dialects in New Mexico, 3 known African languages in Virginia…

The canon that begins with the Spanish are exclusively primary sources, for example, our friend from the second post of Select Reading on Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. This version of the story begins with 1492, when Columbus sailed the ocean blue, a singsongy phrase we memorized as a children. Now we teach his “Letter of Discovery,” a glowing, self-congradulatory account alongside a letter from An Account, Much Abbreviated of the Destruction of the Indes” written at the same time by Bartolome de las Casas, who puts Columbus’s atrocities toward the Taino peoples into its appropriate context. It reads like The Purge.

As Nikole Hannah-Jones and others have eloquently argued, one history of the United States begins in 1619, when the White Lion (also Dutch) landed at the English Chesapeake colony at Point Comfort and traded 20-30 African people for provisions. If you haven't read the opening essay “Democracy” or checked out The 1619 Project, head here. In that lineage, we open space for class conversations about how Black Americans perfected American democracy, by fighting to restore self sovereignty and liberation since that time.

Which brings to mind, why go back to the beginning at all? There are only 13 lectures in the semester and (if we start with the Spanish:) 338 years to cover ffs. Couldn’t the class called “American Literature: Beginnings to 1865” rightfully begin with the Declaration of Independence?

What does all this mean for students of American literature? Are they going to get to read “the classics,” or what?

Isn’t this the History department’s problem? What is Literature ?

Why are we starting American literature with this small handful of Europeans? In 1492, 75 million people lived in the Americas in cities and villages; about 60 million lived in Europe. Some of the largest cities in the world at that time were in North America. To decolonize this syllabus would clearly call for us to stop talking about these people in boats and read more about what was happening on shore.

Which brings me to today’s text: the Iroquois Creation Story, as recorded and translated in 1827 by David Cusack. This is how The Norton Anthology of American Literature, 10th Edition begins.

Among the ancients there were two worlds in existence. The lower world was in a great darkness; —the possession of the great monsters; but the upper world was inhabited by mankind; and there was a woman conceived and would have the twin born. When her travail drew near, and her situation seemed to produce a great distress on her mind, and she was induced by some of her relations to lay herself on a mattress which was prepared, so as to gain refreshments to her wearied body; but while she was asleep the very place sunk down towards the dark world. The monsters of the great water were alarmed at her appearance of descending to the lower world; in consequence all the species of the creatures were immediately collected into where it was expected she would fall.

The story of American literature begins here, with childbirth, comfort, and weariness. The sky mother, nearing her time, is comforted by her people who provide for her, and in her weariness, falls asleep.

In the dark place, a turtle appears and offers to support her, giving its back to become a Great Island.

The woman alights on the seat prepared, and she receives a satisfaction. While holding her, the turtle increased every moment and became a considerable island of earth, and apparently covered with small bushes.

One of her unborn infants decides to exit her womb from under her arm — he is breach — and the other tries to stop him. The twins within her womb war with one another, and the mother does not survive. The twins are born in darkness, motherless.

After a time the turtle increased to a great Island and the infants were grown up, and one of them possessed with a gentle disposition, and named ENIGORIO, i.e. the good mind. The other youth possessed an insolence of character, and was named ENIGONHAHETGEA, i.e. the bad mind. The good mind was not contented to remain in a dark situation, and he was anxious to create a great light in the dark world; but the bad mind was desirous that the world should remain in a natural state. The good mind determines to prosecute his designs, and therefore commences the work of creation. At first he took the parent’s head, (the deceased) of which he created an orb, and established it in the centre of the firmament, and it became of a very superiour nature to bestow light to the new world, (now the sun) and again he took the remnant of the body and formed another orb, which was inferiour to the light (now moon).

The mother becomes their sun and the moon, and the turtle, their home. The war between the “good mind” and the “bad mind” is a war between creation and conservatism — the good mind seeks to bring light of new ideas and to make of his mother’s body a “new world” populated with humankind and all the species of animals — the bad mind wants to stay in darkness, and for things to remain unchanged. He makes obstacles — mountains, waterfalls, reptiles — to hinder the abundance and safety of his brother’s creations.

I don’t usually do a bibliography on these posts but there is a lot of information on this debate that I’ve only given the merest summary to. So if you’re interested in re-visiting your own remembered syllabi, please see:

The Island at the Center of the World, by Russell Shorto.

The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story, edited by Nikole Hannah Jones

1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus by Charles Mann

These Truths: A History of the United States by Jill Lepore

The Puritan Origins of the American Self, by Sacvan Berkovitch

The World Turned Upside Down: Indian Voices from Early America, edited by Colin Calloway