Last week:

This week: “Girl” by Jamaica Kincaid (1978)

Next week: Willa Cather, O Pioneers (1913)

Before we begin, I need you to read this poem aloud. If you can, get another few people to read it with you, each of you taking a line or two. I am committed to rendering this poem in spoken word language, out loud, before we talk about it.

It’s a talking poem. It’s a sass back, catch hands kind of poem.

Perhaps that’s why I like teaching it so much. Every time I do, I get to witness a room full of young people wake up this poem and conjure the woman speaking inside it, and then take her measure and bring her down in the subsequent discussion with the passion of young people tired of being told what to do.

I’m not sure when I started teaching this one. It came up regularly in the “Writing and Thinking Week” of the Seminar sequence I taught with the Bard Early College. It pairs well in the curriculum on understanding social norms, identity, and gender. It pairs well with teenagers, too.

Okay, you read it out yet?

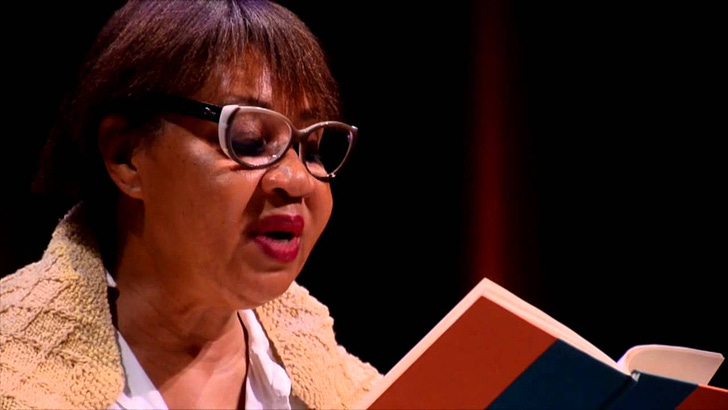

Jamaica Kincaid (b. 1949) does not change her tone as she reads, even as the audience nervous laughs the first time she says “slut you are so bent on becoming” and each time it is repeated. She has said that this poem was written about girlhood on Antigua. Not her girlhood, necessarily, not also not not hers. Kincaid writes a lot of autobiographically-inspired material, which is not actually memoir, but also not not memoir. She’s tricky, so we can’t say that this poem was about young Elaine Cynthia Potter Richardson (her birth name) in the early 1960s and we also can’t say that it isn’t.

Kincaid’s parents sent her from Antigua to Scarsdale, New York to work as an au pair when she was sixteen. Her mother had made sure that she had a classical British colonial education and taught her to read beforehand, and books play a huge role in her autobiography. She writes that they played a large role in her survival as a teen living alone in upstate New York. She has been a professor of literature at Harvard since 1992, and an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters since 2004.

Mostly Kincaid is known for her semi-autobiographical novels, of which there are five, and her nonfiction and writing for The New Yorker, where she was a staff writer from 1974-1996. This poem (or short story, which it has also been anthologized as) appeared first in the New Yorker, in June 1978.

this is how you sweep a whole house; this is how you sweep a yard; this is how you smile to someone you don’t like too much; this is how you smile to someone you don’t like at all; this is how you smile to someone you like completely

This is a “how to” poem — a significant genre that does a lot of work in establishing social norms, in a didactic fashion, and it has a tradition of repetition. It is also a “dramatic” poem since there are clearly two voices in the work. The didactic voice appears to be a maternal elder, a mother or grandmother, and the object of her lesson, a young teenager who speaks in her own defense.

Formally, the elder speaker of the poem relentlessly offers 600+ words of advice and direction and admonishment, with a little shaming thrown in, separated by semicolons. What rhythm that exists is created by repetition. There are two moments in the text when the girl speaks back, separated by italics, and in both cases, the lines appear delayed, as though she has not yet been able to get a word in:

This gives us a chance to understand the relentlessness of the torrent of advice that this poem supplies — it takes a few beats before she has registered that her elder has accused her of singing Benna on Sundays, and now she has to defend herself — but the elder has moved on to fruits in the street, and does not respond to the small voice of dissent, at all. We’re moving on— to buttons.

What gets a laugh from my students and the audience is when the speaker of the poem slut-shames the girl, and this part of it is also the most volatile language in the poem.

on Sundays try to walk like a lady and not like the slut you are so bent on becoming;

I say volatile, because it lights the poem up, bring up a rise in us, and causes the girl to sass back, in futile italics.

For, stuck in between the to-do list of domestic chores and directions on how to do “women’s work”— laundry, sweeping, cleaning, gardening, cooking, shopping, ironing, sewing, fishing, nursing, pleasuring, smiling — we get the social guidelines, the sharp boundaries of containment commonly called “modesty.” There are Christian aspects to this containment, Sunday being one of the repeated words in the poem.

Also stuck in, between the to-do lists and the shaming, is the Caribbean. The culture comes alive in this short poem. It is in the unfamiliar-to-me words, like Benna and doukona, and in the cultural scripts and codes. The poem is an array of information, each line a potential life-path.

Usually, we unpack this poem for an hour in class. If you spend an hour studying it, the life paths just keep stretching out in front of you. What do you notice about the grammar of the speaker. Why does Kincaid do that? What about how it looks on the page? What repetitions are speaking to you? How does the tone land? Why? Does it seem trapped in a past that is inaccessible to you, or can you also see yourself taught in these lines?

And then I ask them to take one of these semi-coloned “lines” and use it to launch into their own “how to” poem. A good way for us to get to know each other — what did your elders teach you about how to move through the world? Which one of Kincaid’s lines did you wish someone had also taught you how to do?