I found myself incorrigible with respect to Order

Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography, Part III (1784, 1818)

Last week:

This week: Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography (1784, 1818)

Picking up on last week’s notes about notes, I thought I would stop for a moment to consider habit tracking. What is it about my algorithmic patterns that guides my devices to show me habit tracking software ads every damn day? “Disappear for 6 months and return unrecognizable! Download ‘Greatness’ today.”

The concept of “habit tracking” has a strong lineage in American culture, by way of Benjamin Franklin (1705-1790). Through his influence, this concept has its roots in two powerful mythologies: the intellectual legacy of John Locke and Descartes and the “American dream.” In drawing this line:

Franklin+the Enlightment+Bootstraps Myth = Greatness

I return to a moment in Franklin’s famous autobiography, Chapter 9, cautiously entitled “Plan for Attaining Moral Perfection.” This section was written in 1788 and published in Paris in 1791 and in the United States in the early nineteenth century in various states and editions, finally landing as the text we know in 1910. The story of the manuscript is a complex one, as it was both a private and public document of a public man who dressed and acted as if he were in private.

The plan for attaining moral perfection is as follows:

It was about this time [c. 1728] I conceived the bold and arduous project of arriving at moral perfection. I wish'd to live without committing any fault at any time; I would conquer all that either natural inclination, custom, or company might lead me into. As I knew, or thought I knew, what was right and wrong, I did not see why I might not always do the one and avoid the other. But I soon found I had undertaken a task of more difficulty than I had imagined. While my care was employ'd in guarding against one fault, I was often surprised by another; habit took the advantage of inattention; inclination was sometimes too strong for reason. I concluded, at length, that the mere speculative conviction that it was our interest to be completely virtuous, was not sufficient to prevent our slipping; and that the contrary habits must be broken, and good ones acquired and established, before we can have any dependence on a steady, uniform rectitude of conduct. For this purpose I therefore contrived the following method.

He goes on to explain that he made a little book and each of the virtues has its own page. The lines above were drawn in red ink, so that each day he

“might mark by a little black Spot every Fault I found upon Examination, to have been committed respecting that Virtue upon that Day.”

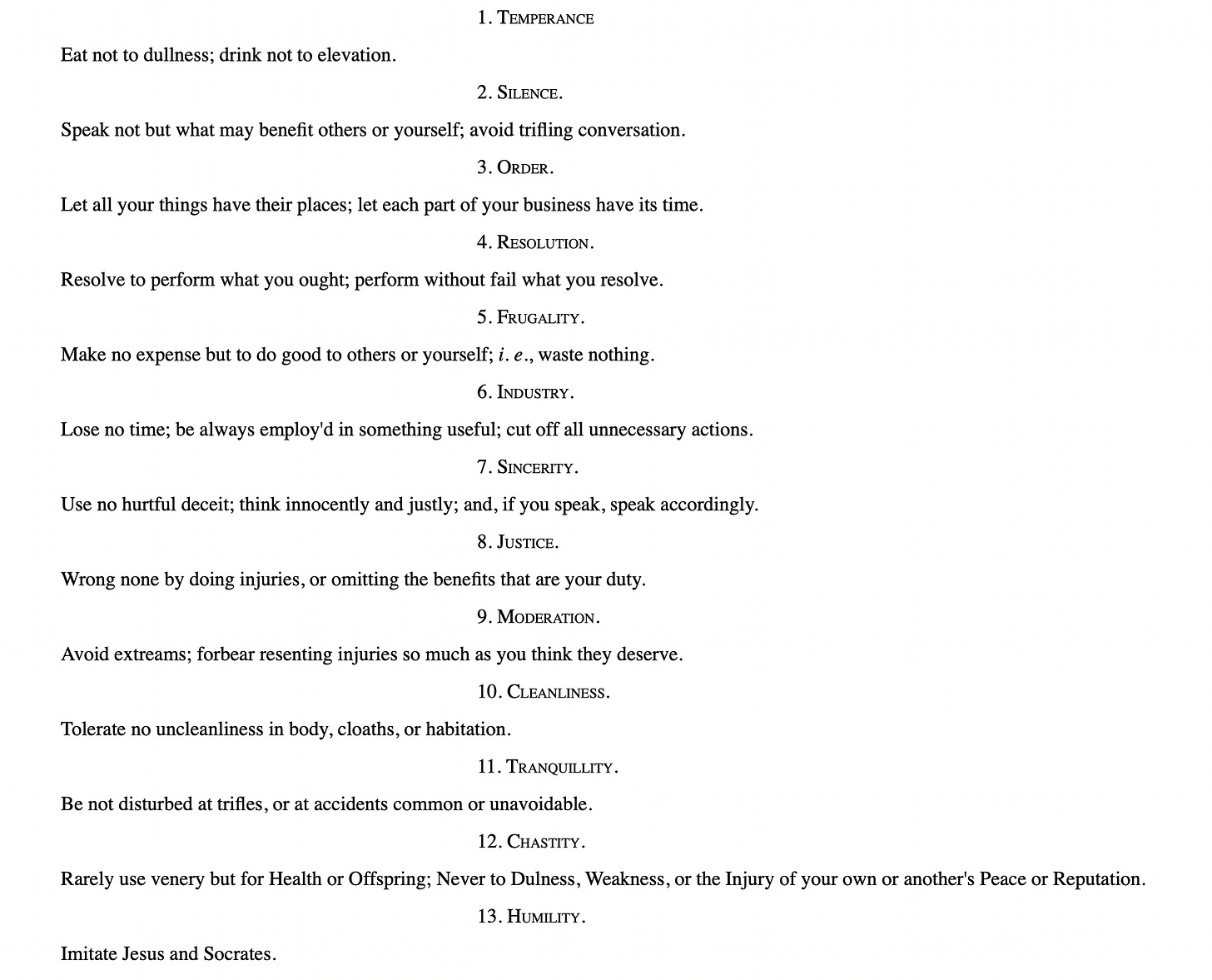

These are the virtues he tracks, for your edification:

So, why a page per virtue, if he is planning to track all of these 13 virtues at the same time? This is due to the fact that he found he could only keep front of mind one at a time. Habit ordering and stacking aligns with nearly all the digital habit trackers out there — James Clear fans eat your heart out! — it is not possible to begin 13 habits at once.

The idea was that he would give his full attention to one virtue at a time, “my great guard was to avoid even the least offense” for the one virtue and let the other 12 slide. Go the normal course. His dream was that if he gave his full attention to one, he would emerge with a clear line at the top, with the usual mess of Spots beneath. Then the next week he would go on to conquer the next virtue, and hopefully emerge with two clean lines. And so forth for 13 weeks, repeated four times a year.

And like him who, having a garden to weed, does not attempt to eradicate all the bad herbs at once, which would exceed his reach and his strength, but works on one of the beds at a time, and, having accomplish'd the first, proceeds to a second, so I should have, I hoped, the encouraging pleasure of seeing on my pages the progress I made in virtue, by clearing successively my lines of their spots, till in the end, by a number of courses, I should be happy in viewing a clean book, after a thirteen weeks' daily examination.

He goes on to explain the order — since conquering Temperance would open an easier path to Silence, it comes first.

Temperance first, as it tends to procure that coolness and clearness of head, which is so necessary where constant vigilance was to be kept up, and guard maintained against the unremitting attraction of ancient habits, and the force of perpetual temptations. This being acquir'd and establish'd, Silence would be more easy; and my desire being to gain knowledge at the same time that I improv'd in virtue, and considering that in conversation it was obtain'd rather by the use of the ears than of the tongue, and therefore wishing to break a habit I was getting into of prattling, punning, and joking, which only made me acceptable to trifling company, I gave Silence the second place. This and the next, Order, I expected would allow me more time for attending to my project and my studies. Resolution, once become habitual, would keep me firm in my endeavours to obtain all the subsequent virtues; Frugality and Industry freeing me from my remaining debt, and producing affluence and independence, would make more easy the practice of Sincerity and Justice, etc., etc.

Humility is the last to conquer, for as he admits — it is near impossible to subdue pride.

According to his Autobiography, Franklin carried on with this project for years. He swapped out the little book with a more durable paper and drew his black marks in pencil so that he could erase and start again, at first four times a year, then once a year, then every few years, and finally, when life and statecraft made him too busy for this level of discipline, he kept the little book with him as a reminder. In this Autobiography, he is explaining this project begun in his early twenties, and remembering it in his eighties. I picture him writing in bed with this little book on his bedside table. I realize that is unlikely, given the state of his personal papers post-war (“I found myself incorrigible with respect to Order”), but nevertheless, he could recover from memory the format and definitions. Let’s face it — he is proud of this achievement, as well he should be.

I was surpris'd to find myself so much fuller of faults than I had imagined; but I had the satisfaction of seeing them diminish.

Okay, for anyone who has seriously embarked on a 13 weeks challenge of this magnitude (and there are many people who use Franklin’s method today), you and I both know: moral perfection is a lie.

The data are already always cooked. There is no such thing as raw data when it comes to virtue tracking. The data that Franklin reports here are subjectively defined virtues, subjectively tracked as empirical data, then glowingly recalled 62 years later as part of a legacy building project. You get where I am going with this? We read these data as reflective of Franklin’s inner growth as a temperate, silent, ordered, resolute, humble man, because that is the project of this Autobiography, to tell the narrative of Ben Franklin as a man of virtue, science, and personal growth.

Franklin had been a member of the Royal Society during its heyday, and corresponded avidly with its members. The thinkers of his day, now known as the “empiricists,” focused upon a reliance on the testimony of nature, revealed through the scientific method of systematic observation of repeatable experimentation, and — crucially — not human testimony. This is a gross oversimplification, but what I want to get out of this is how seductive order can be. What Franklin attempts with his little book is to take the human testimony of his own personal growth, and to make it quantifiable. He gives us a believable method for human perfectibility through the exercise of reason. He sells the dream of making the messiness of human experience quantifiable as data, in order to make it knowable. The dream of “Know Thyself,” here the little marks he makes at the end of the day, which would yield to interpretation. All the messiness of life contained as a comforting, beautiful infographic. As he said, he found comfort in seeing the little marks diminish over time.

Elsewhere in the Autobiography, Franklin gives us this little warning, to take everything he writes with a bucket of salt:

So convenient a thing is it to be a reasonable creature, since it enables one to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to do

So convenient indeed!

The joy of reading Benjamin’s Autobiography is its tone of jocular familiarity. He is so approachable. The habit tracking plan is an inspiring private anecdote of an endearing historical figure, if it ended there. But his little form is used as an apparatus of the American Dream, as it perfectly encapsulates the idea that the 23-year-old Franklin pulled himself up by “his bootstraps” to sit in the rooms of power. For many Americans, this is the only part of the Autobiography that they have read. Certainly, this “greatness” is what the digital trackers are promoting. Track your habits, and you will get the life, the body, the afterlife you deserve. In just 13 weeks!

The science is this: goal tracking works, because what we focus on, we improve.

Franklin interprets his data for us at the end of the chapter, closing with a list of failures that is comforting and humorous. Order was his bugbear (as it is mine):

In truth, I found myself incorrigible with respect to Order; and now I am grown old, and my memory bad, I feel very sensibly the want of it. But, on the whole, tho' I never arrived at the perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining, but fell far short of it, yet I was, by the endeavour, a better and a happier man than I otherwise should have been if I had not attempted it

He writes that order proved near impossible to maintain, even for a week, and for this I give him so much gratitude. He says that he could never keep the schedule he’s credited with, and that his papers and other items were continually a mess.

Here is “Franklin self-improvement schedule”:

The man who is credited with giving us such one liners as, “The morning has gold in its mouth,” and “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise” has admitted that such a schedule is difficult to maintain. Others are always demanding of your attention, your time is not always your own. I am always so envious, too, of the 5am club, and I’ll admit my day is better when I follow this schedule, but damn it is hard to maintain.

To this industry of self-improvement trackers and productivity hacks, Franklin sends this message:

that a perfect character might be attended with the inconvenience of being envied and hated; and that a benevolent man should allow a few faults in himself, to keep his friends in countenance.

Keep a few faults, it makes you a better friend.

Select Reading is a *free* weekly publication of my lecture notes from twenty years of teaching American Literature. The semester starts up again soon, so come back to class! To receive new posts in your inbox, consider becoming a free subscriber. You can also support this work with a paid subscription, if you want to leave a tip, or by sharing the articles you like. Thanks!