I left the woods for as good a reason as I went there.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden or Life in the Woods (1854)

Last post:

Not all readers make it to the end of Walden, or Life in the Woods (1854), since a few dozen pages of snoozy meditations on masonry, quasi-Eastern philosophy, and pea shoots come between it and the famous lines about “living deliberately.” The short chapter entitled “Conclusions” is one of my favorites, and where I go for solace and wisdom.

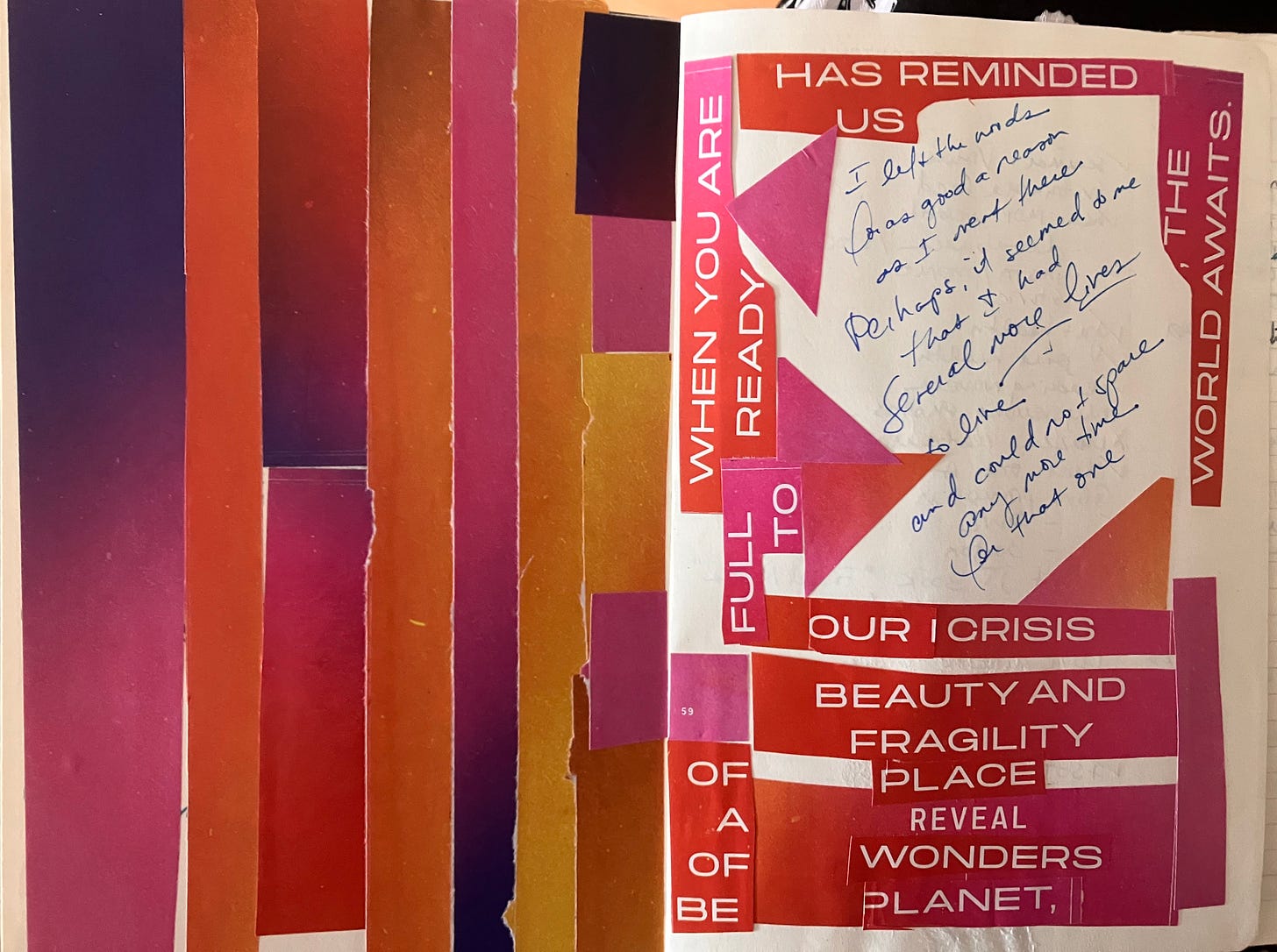

This quote that I keep on the flyleaf of my journal is a reminder that life offers us endings and beginnings:

I left the woods for as good a reason as I went there. Perhaps it seemed to me that I had several more lives to live, and could not spare any more time for that one.

When Thoreau left the woods in September 1847 at 30 years of age, he had experienced two life-changing events in those two years, two months, and two days at Walden Pond. The first was the experiment in living close to the bone that he had arranged for himself at the cabin. The lessons he learned and reported in those years would forever be associated with his name. The other was his decision in July 1846 to apply what he had learned about integrity, authenticity, and bravery with a small act of civil disobedience, to not pay his poll tax in protest to the threat of an expansion of slavery with the Mexican-American war. His words in response to those experiences would be world-changing and inspiring for millions, famously Mahatma Gandhi and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King. I hardly ever meet a person who has not heard of Walden or “Civil Disobedience,” or both.

Thoreau lost his beloved brother and best friend to tetanus in the years prior to living at Walden pond, and the death of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s son Waldo the same year also affected him deeply. We know Thoreau had already contracted the tuberculosis that would one day take his life by the time he went to the woods. I am older now than Thoreau was when he died. So when he writes that he intends “to live deep” and to live with only the essentials in order to discover what was truly essential, these were not philosophical considerations or scientific observations. He wanted to live in such as way so that when he came to die, he knew he had lived life authentically:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.

So when he says at the end of the book that he “could not spare any more time for that one,” that life in the woods, I can recognize the scars of grief in between the lines. I too have a sense of my own mortality that was hard won. He means it — life is so dear that we cannot waste a moment in a rut, living over experiences that have already run their course. Death, he wrote in his journal, is only beautiful if we see it as law and not accident. The years are short— it is important to leave the woods in order to begin the next chapter. What a way to end a book. What a gift to give.

Perhaps, he writes, there are more lives to live and that is a good enough reason to leave behind what lives we have built so far, just to see what happens next. I wonder if he meant us to read a comma after the word “Perhaps” — and if he meant for us to understand that he is mucking about in his own self-deception when he writes “it seemed to me.” When I copy these words into the new journal, I feel a little superstitious. Backing into the certainty that there will be “several more lives more lives to live,” Thoreau reminds us that life is short and uncertain, and that we should know when it is time to move on to the next chapter. In putting all these perhapses and seemed-s in the chapter, Thoreau, it seems to me, is giving himself a little grace. A hat tip, that the sage of Walden is not above second guessing himself, too. Ending something is hard.

A lot of the chapter is about mindset, and talking ourselves into living life deliberately — even if we are in poverty, even if we are not successful, even if we court solitude when we speak our truth. I love how much room Thoreau gives to the very human emotions of doubt, fear, and conformity in what is supposed to be the triumphant Conclusion chapter. Here’s another classic:

I learned this, at least, by my experiment; that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours. He will put some things behind, will pass an invisible boundary; new, universal, and more liberal laws will begin to establish themselves around and within him; or the old laws be expanded, and interpreted in his favor in a more liberal sense, and he will live with the license of a higher order of beings. In proportion as he simplifies his life, the laws of the universe will appear less complex, and solitude will not be solitude, nor poverty poverty, nor weakness weakness. If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.

Notice the “at least”? The imperatives come later. First he says, my experiment in living deliberately has yielded me this truth, at least — that I can successfully imagine and build my life according to my dreams, and the road will rise to meet me. The at least tries to convince us of what he has come to trust as truth, that the very minimum of manifestation woo-woo is true. The Thoreau-esque pilgrim Michael Singer, in The Surrender Experiment arrives at the same conclusion. We need only to trust and “advance,” to surrender to the expansive law of the universe. Take the first step in the direction of the dream, and in doing so, you will cross and invisible boundary between then, the person you were, and now, the person you are.

The trick is knowing when it is the right time is to advance. As he says earlier in the chapter, we often get into a rut, and it would have been possible for him to stay in the Walden woods forever passing another happy season between cabin and lake, lake and cabin. Sometimes, too, the future we hoped for is not ready for us yet.

Why should we be in such desperate haste to succeed, and in such desperate enterprises? If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away. It is not important that he should mature as soon as an apple-tree or an oak. Shall he turn his spring into summer? If the condition of things which we were made for is not yet, what were any reality which we can substitute?

When is the right time to leave and start anew? By stepping out in the direction of our dreams, do we threaten to cut short something that is not yet matured, not yet ready? I really struggle with this.

The last anecdote he shares in response to this conundrum is so charming, I can’t skip over it.

Every one has heard the story which has gone the rounds of New England, of a strong and beautiful bug which came out of the dry leaf of an old table of apple-tree wood, which had stood in a farmer’s kitchen for sixty years, first in Connecticut, and afterward in Massachusetts,—from an egg deposited in the living tree many years earlier still, as appeared by counting the annual layers beyond it; which was heard gnawing out for several weeks, hatched perchance by the heat of an urn. Who does not feel his faith in a resurrection and immortality strengthened by hearing of this? Who knows what beautiful and winged life, whose egg has been buried for ages under many concentric layers of woodenness in the dead dry life of society, deposited at first in the alburnum of the green and living tree, which has been gradually converted into the semblance of its well-seasoned tomb,—heard perchance gnawing out now for years by the astonished family of man, as they sat round the festive board,—may unexpectedly come forth from amidst society’s most trivial and handselled furniture, to enjoy its perfect summer life at last!

While we can never know if the time is right to come forth and claim the “the life imagined,” we can trust that when the unexpected hour comes, when we pass that invisible boundary from then to now, it will be the right time. It will be summer.

So beautiful…. I think you, Gram, and I always enjoy Thoreau at Walden Pond. It just rings true. The older I get, the more I can look back and see how life unfolded. And we somehow get a feeling that it’s just time to start a new chapter, a new life!