It’s a shameful, wicked, abominable law, and I’ll break it, for one, the first time I get a chance.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852)

This week I want to discuss Uncle Tom’s Cabin, by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) an unlikely catalyst for two big pivots in my career. The first was my move away from researching daguerreotypes and Hawthorne (snooze!) to writing about daguerreotypes and abolition (yay!). I would never swap out my first love, early photography, but as a nineteenth-century Americanist, I was glad to move into the more robust and diverse literature around antislavery. I first read Uncle Tom’s Cabin in a graduate course on US Reform Literature (way back in 2004, ffs) and found this narratorial comment in the introduction to the titular character, Uncle Tom, top of chapter four:

“At this table was seated Uncle Tom, Mr. Shelby’s best hand, who, as he is to be the hero of our story, we must daguerreotype for our readers. He was a large, broad-chested, powerfully- made man, of a full glossy black, and a face whose truly African features were characterized by an expression of grave and steady good sense, united with much kindliness and benevolence. There was something about his whole air self-respecting and dignified, yet united with a confiding and humble simplicity.”

I wrote a rather ponderous chapter on this passage for my dissertation, which argued for a “photographic” style of writing in abolitionist literature in the 1850s. I won’t bore us with that recitation here, but suffice it to say, I pivoted to abolitionism and away from Romanticism and never looked back. My first 7 years of research transformed by a single word: the noun daguerreotype here used as a verb, to refer to a descriptive mode. Savvy readers will notice that the characteristics that Stowe “daguerreotypes” are not all photographable.

The other pivot is more recent — a fantastic opportunity popped up on my feed in the spring of 2021 in the Netherlands. I made the short list for the campus interview. Big problem: covid prohibited travel to Europe. The search committee offered a workaround that also felt like one of the secret box challenges on Masterchef. Lay out the gingham cloth with these ingredients: I had 25 minutes; requested a seminar-style course; online using MS Teams; approx. 12 students and 8 faculty observers; and the topic must be the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, with no confirmation what percentage of the class had read it. I got the position.

I decided that I would lead a pre-reading introduction session, so that it wouldn’t matter if the students had read the novel yet. Maybe that is also you? Fewer and fewer readers pick up this novel (more on that in a sec). By way of an introduction, allow me three points:

serial publication: Uncle Tom’s Cabin was serially published, in the National Era, an antislavery newspaper. Serial publications have generic qualities to keep in mind — sometimes authors were paid by the word or the column, so they used a lot of them. Sometimes authors were writing pages as the pages were published, staying just one or two weeks ahead of their serial’s publication schedule, even responding to reader comments or redirecting to popular topics, rather than the agonizing write-the-whole-novel and revise it endlessly that become the norm in the 20th century. And it was understood that parts of the novel could be missed, or read out of order, if say your Aunt Lydia forgot to save you a copy of issue #44. Authors tended to account for this stylistically, by leaning on stereotypes and repetitions to get the readers through. The subtitle was changed from the serial publication, from “A Man who was a Thing” to the less explosive “Life Among the Lowly” for the book volume.

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. (Read it at the link) Stowe widely cited the Fugitive Slave Law as the catalyst for this novel. Part of the Compromise of 1850, this law was a misguided attempt to save the United States from disunion but had the effect of radicalizing antislavery activists. People in the free states, regardless of their political opinions, could be fined or jailed for aiding a person who was in the act of fleeing enslavement, or suspected of having done so. This law implicated the white domestic sphere in maintaining slavery and this transgression brought many Northern white women into the antislavery movement. These people are Stowe’s audience.

These women are illustrated in the novel, in chapter 9: “In Which It Appears That a Senator Is But a Man.” Senator Bird of Ohio and his wife are enjoying a moment of quiet after the kids are down, and she asks:

“Well,” said his wife, after the business of the tea-table was getting rather slack, “and what have they been doing in the Senate?”

Now, it was a very unusual thing for gentle little Mrs. Bird ever to trouble her head with what was going on in the house of the state, very wisely considering that she had enough to do to mind her own. Mr. Bird, therefore, opened his eyes in surprise, and said,

“Not very much of importance.”

“Well; but is it true that they have been passing a law forbidding people to give meat and drink to those poor colored folks that come along? I heard they were talking of some such law, but I didn’t think any Christian legislature would pass it!”

“Why, Mary, you are getting to be a politician, all at once.”

“No, nonsense! I wouldn’t give a fig for all your politics, generally, but I think this is something downright cruel and unchristian. I hope, my dear, no such law has been passed.”

“There has been a law passed forbidding people to help off the slaves that come over from Kentucky, my dear; so much of that thing has been done by these reckless Abolitionists, that our brethren in Kentucky are very strongly excited, and it seems necessary, and no more than Christian and kind, that something should be done by our state to quiet the excitement.”

“And what is the law? It don’t forbid us to shelter those poor creatures a night, does it, and to give ’em something comfortable to eat, and a few old clothes, and send them quietly about their business?”

“Why, yes, my dear; that would be aiding and abetting, you know.”

Mrs. Bird is described as a “blushing, timid” woman “of about four feet.” But in defense of helpless kittens, her sons remember, she could be fiercely protective. Stowe suggests that these “poor creatures” [sic] are in need so similar protection, and Mrs. Bird stands up to her husband’s expediency:

On the present occasion, Mrs. Bird rose quickly, with very red cheeks, which quite improved her general appearance, and walked up to her husband, with quite a resolute air, and said, in a determined tone,

“Now, John, I want to know if you think such a law as that is right and Christian?”

“You won’t shoot me, now, Mary, if I say I do!”

“I never could have thought it of you, John; you didn’t vote for it?”

“Even so, my fair politician.”

“You ought to be ashamed, John! Poor, homeless, houseless creatures! It’s a shameful, wicked, abominable law, and I’ll break it, for one, the first time I get a chance; and I hope I shall have a chance, I do! Things have got to a pretty pass, if a woman can’t give a warm supper and a bed to poor, starving creatures, just because they are slaves, and have been abused and oppressed all their lives, poor things!”

At the time, as we can see in the narrator’s little comment, that Mrs. Bird taking a stand “quite improved her general appearance.” This is called metalepsis, or a transgression of the narrator into the narrated text (definition from Gerard Gennette), and Stowe is a Metaleptic Queen. To bring shame down on her husband, to stand up to him in this way, was big moves in 1850. Only the husband has the vote in 1850, and it was thought that women convinced their husbands of the moral vote. Here it is in action — with a claim to higher law ideology (remember, from Thoreau?). This woman, the wife of a Senator, has claimed that she will break the law, soon as she can.

In the logic of the sentimental novel, a fugitive Eliza shows up that very evening, carrying her little boy Henry, who reminds Senator Bird of his recently deceased son. His heart melts. He breaks the law in helping them to safety. This is a level of success that Stowe’s readers can aspire to.

When we read this scene now, it loses half its power in the poisoned apple of dehumanization (“creatures” pops up multiple times to refer to people), and Mrs. Bird’s pity. Which brings me to the third point I want to make today:

popular → pejorative. So, as you are probably already aware, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was astoundingly successful as a publication, both in serial form and as a book, reaching one million American homes by the end of 1853, its first year in print. (For comparison, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was in 50,000 home in eight weeks; that is equal to the total sale of all of Herman Melville’s novels during his lifetime. Take that Ahab.) Then, it became a blockbuster theater production and minstrel show, heavily leaning on conventions such as blackface to tell the story of Uncle Tom. And then, it engendered an industry of merch and advertising that made Aunt Chloe (the mammy figure) and Uncle Tom and Topsy into stereotypes. Due largely to these stereotypes of the servile central figure of “Uncle Tom” and an influence article by James Baldwin (“Everybody’s Protest Novel”) in 1949, the phrase “Uncle Tom” came to be a pejorative term used to describe a Black man who is subservient to whites, a slur that has eclipsed the original character.

Stowe’s pitying tone, dehumanizing rhetoric, and colorism in the novel have made it a difficult read in the 21st century. Like reading J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series after 2019, we tread more carefully now. To read Uncle Tom’s Cabin now is to hold in one hand, a novel that is a powerful, moving, and sometimes humorous romp of a read, a true page-turner, and a political novel that was enormously influential and objectively effective, a feat that political fiction often aspires but rarely attains, and that is by a woman writing into a political quagmire that would have happily excluded her. And we hold, on the other hand, a novel that has a clear hierarchy of races, a clear and biased understanding of white womanhood, an evangelical outlook, and more than one outright offensive passage.

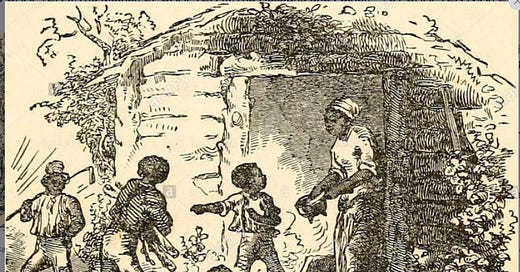

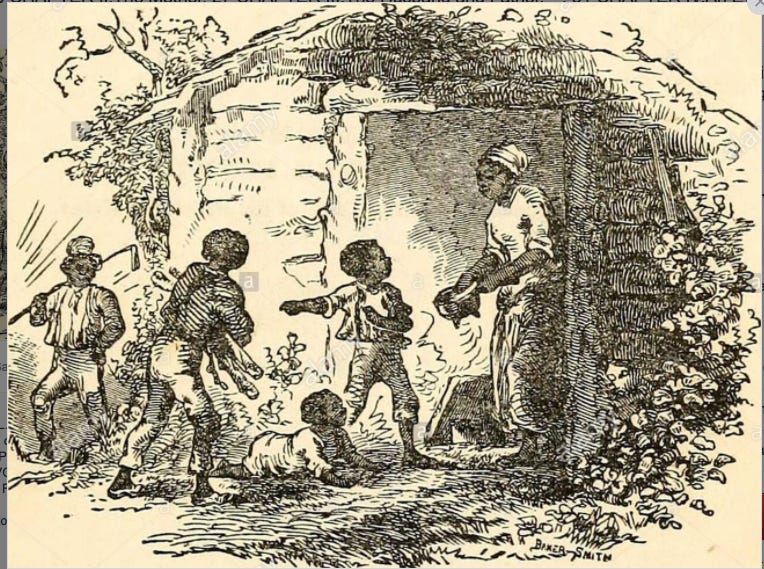

I think all this can be read into the frontispiece illustration by Hammat Billings. A frontispiece decorates the title page and informs reader on the major themes of a text, but this one illustrates a reunion scene that doesn’t happen in the novel. [Spoiler!] The image on the cover offers both hope and disillusion, centers women’s experience, and positions Tom just out of sight — his face difficult to see.

It’s clear that this scene was also important to Tom, because he recalls in in the narrative, in Chapter 14 as he is nearing the New Orleans slave market:

“He saw the distant slaves at their toil; he saw afar their villages of huts gleaming out in long rows on many a plantation…—and as the moving picture passed on, his poor, foolish heart would be turning backward to the Kentucky farm,…the little cabin, overgrown with the multiflora and bignonia. There he seemed to see familiar faces of comrades, who had grown up with him from infancy; he saw his busy wife, bustling in her preparations for his evening meals; he heard the merry laugh of his boys at their play, and the chirrup of the baby at his knee; and then, with a start, all faded, and he saw again the canebrakes and cypresses and gliding plantations, and heard again the creaking and groaning of the machinery, all telling him too plainly that all that phase of life had gone by forever.”

Henri Bergson writes in Matter and Memory (1896), “To call up the past in the form of an image, we must be able to withdraw ourselves from the action of the moment, we must have the power to value the useless, we must have the will to dream. Man alone is capable of such an effort.” Frederic Douglass in “Lectures on Pictures” wrote that “the power to make pictures belongs to man exclusively” (1861) So my takeaway: the distinguishing human characteristic of memory invoked during “the action of the moment,” strikes at the heart of debates surrounding humans as property, demonstrated here as occurring within the interiority of Uncle Tom, who is “the man who was a thing.” We can’t see his face, but when we see this scene at the cabin door reflected in his memories, it underscores his humanity — right before he is sold.

I think Stowe offers us a good site for reflection on the role of the ally. She loves her hero. She wrote into a political battle, and changed its tenor by her wits and quick pen. There was a law that she disagreed with and she wrote a whole dang novel to prove its ignominy. And she brought with her all the prejudice and racialism that characterized her world, and made slavery possible in the first place.

I have a lot more to say on this book, but we will leave it for another day — maybe after you’re done reading it. ;)