Last Week: Sarah Orne Jewett, “A White Heron” (1886)

This week: Stephen Crane, The Red Badge of Courage (1895)

Next week, Jesmyn Ward, Salvage the Bones (2011)

Dear readers, I packed the wrong text home with me last night, so I cannot talk to you about the devastatingly gorgeous Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward as it is sitting back in the office on campus. I simply cannot do that novel justice if I don’t have it in front of me.

This week, I lectured about four texts to three classes: Stephen Crane, The Red Badge of Courage, Jesmyn Ward, Salvage the Bones, Toni Morrison Beloved, and Walt Whitman, “Vigil Strange I kept on the Field One Night.” (I’m planning to get around to writing about all of them at a some point on here.) There is something marvelous and strange about this work of reading and talking about reading, that asks that we spend our imagination (and, in my blessed case, my working hours) immersed in war, sweating and bleeding on the battlefield or behind 124 Bluestone Road, stranded in an attic in The Storm, finding paths through grief to survival and love, to face unimaginable trauma — meanwhile, our bodies are going about our real lives. The class ends and we step free of the war and the hurricane, and back into a sunny springtime morning, one week before midterms.

A privilege of good mental health is to be able to compartmentalize these worlds into an experience of art and “real life”; fiction and fact; past and present. To stay calm in the face of the storms. And yet, and yet. We read together to get a little lost, right? We read to understand and feel what it was to be in those situations. Class discussion demands that we think about the thing in terms of who we are, now, as well as who they were, then. We’re learning a little from every read through, and these worlds do order our steps, sometimes. Sometimes I am Bastian, crying out into the rain for the Empress, and sometimes he and I throwing the book at the wall. (That’s a “The Never-ending Story” reference, my young friends.)

Which brings me to one of these books, and that is The Red Badge of Courage, which is a book that I am always happy to snap shut and throw at the wall.

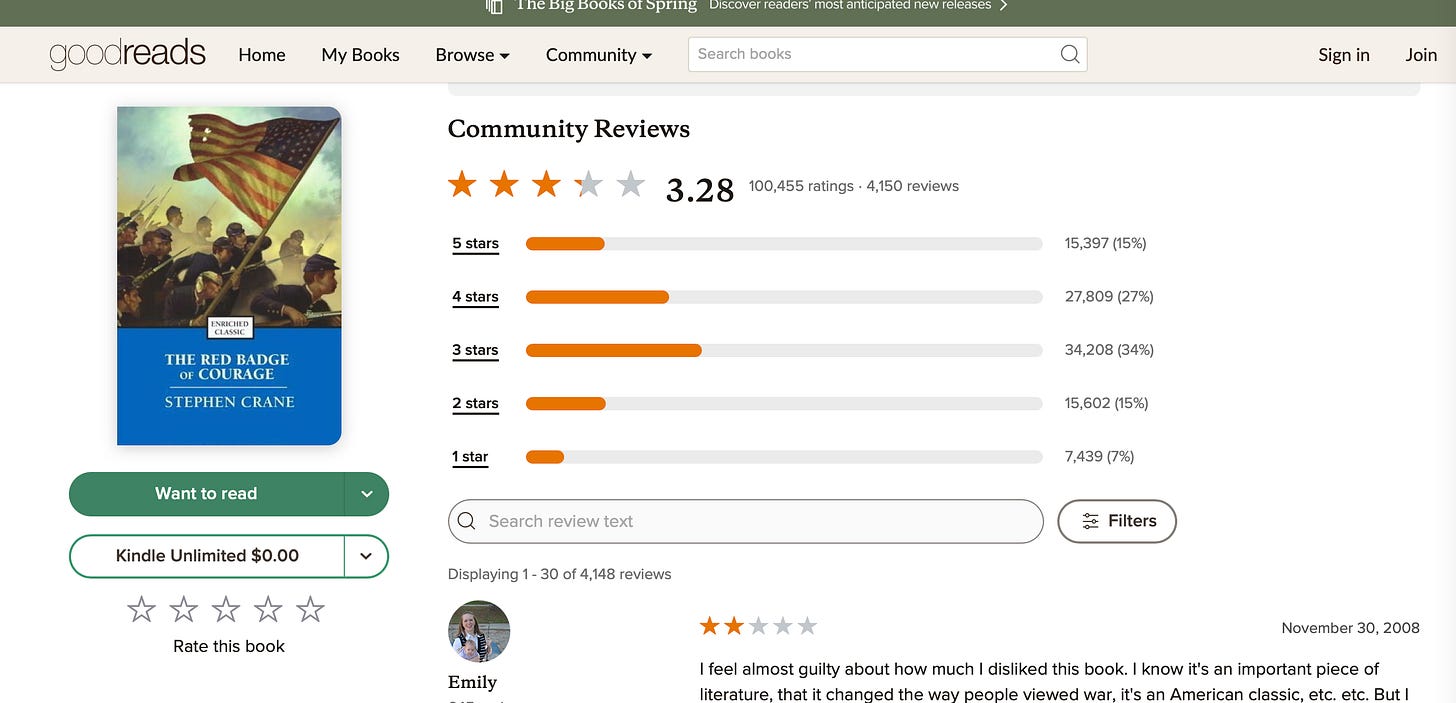

Don't get me wrong, I am a fan of Stephen Crane — I consider him a virtuoso of perspectival fiction and wild character of the literary canon. As one of my students pointed out, the Goodreads rating for this novel is half and half — and it’s not a book for everyone, and yet is is fairly often the assigned reading. Every year I toggle between assigning this book and its older sister, Maggie, a Girl of the Streets.

No, I compartmentalize my reading experience of Henry Fleming on a battlefield because I get sick of being in his head and I just want to sit down.

Literary Impressionism, for which The Red Badge of Courage is used as exhibit A, is a style of narration that is related to Psychological Realism, aka Henry James. It is cousins with the art movement — the author attempts to make a Monet or Van Gogh in words, rather than paint. The reader is placed at the same level and state of mind as the confused — and in this case, naive — characters who serve as the central consciousness for the narrator. The narrator records the “impressions” of the central consciousness, his sensory experiences, his mental state, without interpretation. That part is up to you, as the reader to make sense of. Just as in the painting style — sometimes you have to step back a few paces to understand what you are looking at.

And like Impressionist painting, this literary style is defined by a desire to capture the fleeting, sensory effect of a scene or subject matter through the moment by moment “impressions” left on the consciousness. In place of loose brushstrokes, literary impressionists focus on descriptions of color and light and mood. As the art critic Michael Fried wrote, “If literary impressionism is anything, it is the project to turn prose into vision.”

Here is the opening paragraph:

The cold passed reluctantly from the earth, and the retiring fogs revealed an army stretched out on the hills, resting. As the landscape changed from brown to green, the army awakened, and began to tremble with eagerness at the noise of rumors. It cast its eyes upon the roads, which were growing from long troughs of liquid mud to proper thoroughfares. A river, amber-tinted in the shadow of its banks, purled at the army’s feet; and at night, when the stream had become of a sorrowful blackness, one could see across it the red, eyelike gleam of hostile camp-fires set in the low brows of distant hills.

If you went to middle school in the United States back in the day, you probably already know this paragraph, and you might even have a few ideas about it surfacing for you. It has the unmistakable shape of a school essay on “the use of color symbolism in TRBC” or “the personification of the army in TRBC.” We’re not going to do all that all over again, okay? Instead, let’s re-read this passage as a painting. It looks like a giant landscape, with curves of road and river through the middle third, and a menacing camp set up on the far right; it had recently been night, so the sky transitions left to right as this one long day begins.

The aspect of this style of narration is that we are stuck in the mindset of the character, and once we’re there, we must endure unreliable, broken, or mistaken information, forever carrying the biases of the character into the action of the plot.

We meet Henry, and his biases, as “the youth” once he receives the rumor that there is going to be, finally, a battle.

The youth was in a little trance of astonishment. So they were at last going to fight. On the morrow, perhaps, there would be a battle, and he would be in it. For a time he was obliged to labor to make himself believe. He could not accept with assurance an omen that he was about to mingle in one of those great affairs of the earth.

He had, of course, dreamed of battles all his life—of vague and bloody conflicts that had thrilled him with their sweep and fire. In visions he had seen himself in many struggles. He had imagined peoples secure in the shadow of his eagle-eyed prowess. But awake he had regarded battles as crimson blotches on the pages of the past. He had put them as things of the bygone with his thought-images of heavy crowns and high castles. There was a portion of the world’s history which he had regarded as the time of wars, but it, he thought, had been long gone over the horizon and had disappeared forever…

He had burned several times to enlist. Tales of great movements shook the land. They might not be distinctly Homeric, but there seemed to be much glory in them. He had read of marches, sieges, conflicts, and he had longed to see it all. His busy mind had drawn for him large pictures extravagant in color, lurid with breathless deeds.

But his mother had discouraged him. She had affected to look with some contempt upon the quality of his war ardor and patriotism. She could calmly seat herself and with no apparent difficulty give him many hundreds of reasons why he was of vastly more importance on the farm than on the field of battle.

The battle dreams won out. Here again is a reminder of the power of stories. He read his Homer and his history books and he has set up in his mind an idea, gorgeous painting, of what it means to be a hero, to step into history. This version of his imagination for himself wins out, against his mother’s calm reasonings.

Stephen Crane grew up reading about the Civil War, which ended before he was born. He admits to being a little lovesick with war ardor himself. But his writing about how it felt to fight seemed so real that actual veterans were surprised to learn that the 23-year-old writer had not fought in the Battle of Antietam, 33 years earlier. The book is historical fiction, but very vague as to the details. It’s a bit cheeky, really. Crane knew the war-nuts and veterans could poke holes in his fiction if he was clear about when and where Henry fought, pointing out the topographical mistakes and upset timelines, and to restore the glory of the officers he pilloried. The story is about war and men, writ large; it matters not where or when “the youth” got his battle scars.

He tried to find a war as a correspondent, to give substance to this idea of war that he had so vividly and convincingly drawn from his imagination, after his sudden and meteoric rise with this novel. It was as if he had surprised himself with the power of his own pen. And his biography is wild, y’all. At one point he went bankrupt with his girlfriend Cora throwing parties pretending to be a Duke in Sussex. At another point, he survived a shipwreck by dropping his belt of gold coins into the sea and washing ashore on a dinghy 30 hours later. He would pretend to be a cowboy in New York City. I wish I could do his life story justice here — he was a character to be sure. He died at the age of 28.

The story takes place over a single day at battle. Henry’s view of the day is severely limited by his status — he doesn’t know or understand the strategy. He is surrounded by smoke, darkness, and bushes that obscure his vision. He hears only rumors, and meets strangers. He is terrified that he is going to “quail and run.” The only thing he hopes to get out of this battle is his pride. He’d rather die than be caught running.

Several hours later, after he’s run and returned, he’s back in the thick of battle. It is not at all like in the movies. “He was at a task” a carpender, making boxes and boxes. A pestered animal, worried by dogs. Everyone is making low “noises with their mouths,” a strange undercurrent of effort and swearing. And “There was a singular absence of heroic poses.” The prose, and the experience it describes, are both relentless.

These happenings had occupied an incredibly short time, yet the youth felt that in them he had been made aged. New eyes were given to him. And the most startling thing was to learn suddenly that he was very insignificant. The officer spoke of the regiment as if he referred to a broom. Some part of the woods needed sweeping, perhaps, and he merely indicated a broom in a tone properly indifferent to its fate. It was war, no doubt, but it appeared strange.

There are another 50 pages of disillusionment to come.

In chapter 24, Henry finally sits down in the safety of a tall grass. After a long day of fighting, he wants to have a think on the day, this game of capture the flag that he has somehow won. “He felt a quiet manhood, nonassertive but of sturdy and strong blood.” “He saw that he was good.” “He was a man.” He has obtained all that he hoped for from the experience, and lived to tell us about it in the most painterly way possible. He is glad that he can look back on the “brass and bombast of his earlier gospels”— those war stories that caused him to enlist — and he discovered that “he now despised them.” The spell broken, “He turned now with a lover’s thirst to images of tranquil skies, fresh meadows, cool brooks—an existence of soft and eternal peace.”

Yet for all that, I can’t help but think that he should have listened to his momma and stayed home.

“Henry, don’t you be a fool,” his mother had replied. She had then covered her face with the quilt.