Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Phillis Wheatley, "On Being Brought from Africa to America"

Last week: “Living like Weasels” from Teaching a Stone to Talk by Annie Dillard (1982)

This week: Phillis Wheatley “On Being Brought from Africa to America” (1773)

Next week: Louisa May Alcott, from Little Women, Chapter 34 “Friend” and Chapter 35 “Heartbreak” (1868)

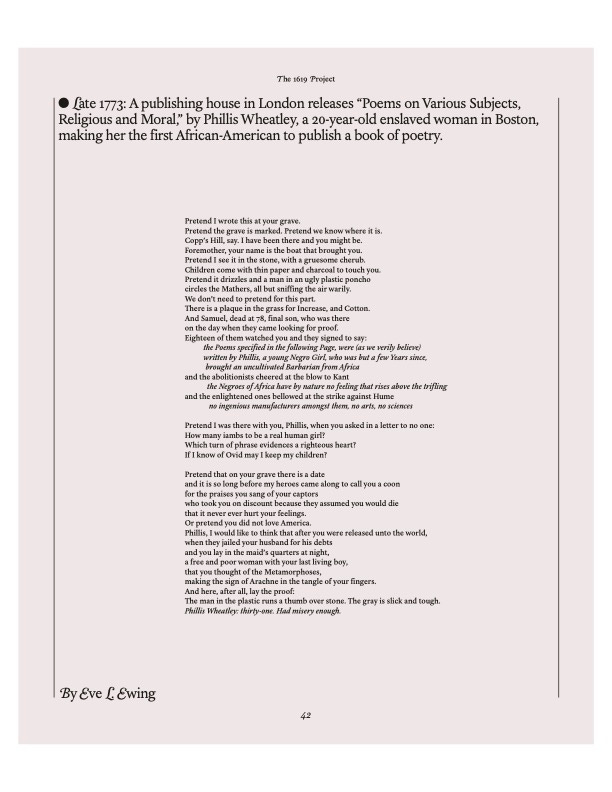

By way of an introduction to the poem “On Being Brought from Africa to America,” I want to offer another poem, “proof [dear Phillis]” by Eve L. Ewing, which first appeared in the New York Times Magazine version of The 1619 Project in August of 2019 (and on p93 & 94 of the book edition). Ewing’s poem is a lament or perhaps, an elegy for Phillis Wheatley:

As the poem tells us, Phillis Wheatley’s first name comes from the slave ship that she arrived on, and her last name from the man, John Wheatley, who purchased her at the dock — back when it was legal for him to buy other people’s futures and bodies at auction to use at will. Phillis Wheatley’s real name is lost to history. She endured the Middle Passage when she was 6 or 7 years old, her age range given because she was missing her two front baby teeth.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Ship database gives us detailed information about that journey. The boat left from Boston harbor with a crew of 8 in November 1760, intending to return with 112 captives for their investors. It left Africa with 95 enslaved people on board. The boat called Phillis arrived in Boston on July 11, 1761. A now debunked “descendent biographer” of the Wheatleys wrote in 1834 that when Phillis arrived, she was “slender” and “frail” and naked except for a piece of “dirty carpet,” which she had fashioned into a makeshift skirt. This is very likely apocryphal or sentimental reporting, but as Eve L. Ewing points out in her poem, John Wheatley “got [her] on discount because they assumed [she] would die.”

These Bostonians taught Phillis how to read and write in English, and then shared books of poems and literature with her. By fourteen, she was publishing poetry in Boston newspapers. In 1773, they went to London to publish a book of her poems.

Phillis Wheatley is known as the first African American poet. As scholar Joanna Brooks pointed out in her groundbreaking article “Our Phillis” (American Literature 2010): thirty-nine poems in the 1773 volume are elegies or occasional poems [poems written about a public event], and at least twelve of them are written about or for white women. These poems are about other women and their grief and experiences., which has garnered a lot of critical notice. When this remarkable book came out, Phillis had still not been manumitted by the Wheatleys. There is hardly anything in the book about her own grief and experiences.

There is a section of Eve L. Ewing’s poem, right there in the middle, that gets to the heart of what I want to say about this, at the desperation, and the loss of this:

How many iambs to be a real human girl?

Which turn of phrase evidences a righteous heart?

If I know of Ovid may I keep my children?

Today’s poem comes from before her first volume, published when she was 16:

This little poem is an intricate dance, a tightrope that the 16-year-old Wheatley walks between “genius” and “unfreedom” as the poet June Jordan wrote in 1985 (Massachusetts Review). She works the tension between form and content, audience and message, until we can see the poem’s meaning push its way through all the sentimentality and expectations and self-righteousness of her readers, the “Christians” of the poem, and hold them, briefly, to account. Although her primary readers were the white women who owned her, we see her moral authority. Although the poem seems somewhat standard for the period, an octave fashioned in four heroic couplets, we can still see how crucial and novel the content is — as the voice of first hand experience.

On first read, it comes across as sanctimonious or sarcastic, or both. Some have even read it as an apology, or self-effacing. Students tend to come around to the side of sarcasm by reading the fourth line over and over. What does it mean that she says outright that she didn’t seek redemption? Was it because she didn’t know it was a thing that she needed? Phillis recites in a singsong-y line: “That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too.”

June Jordan writes in her powerful response to this poem:

But here, in this surprising poem, this first Black poet presents us with something wholly her own, something entirely new: It is her matter-of-fact assertion that "once I redemption neither sought nor knew," as in: Once I existed beyond and without these terms under consideration. Once I existed on other than your terms. And, she says, but since we are talking with your talk about good and evil/redemption and damnation, let me tell you something you had better understand. I am Black as Cain and l may very well be an angel of the Lord: Take care not to offend the Lord!

The next four lines form a counter movement that further illustrate the point.

Not naming names, Wheatley says that “Some” people are racists. Some white people are scornful. She quotes them: “Their colour is a diabolic die.” Putting a quote in a poem in 1771 is like putting something in neon today. This comes across OUT LOUD like a racial slur, like catcalling, like snooty women talking shit over tea, like screed from the pulpit. She has heard this said about herself somewhere and immortalized it here — let it stand and speak for itself, she says.

In the next line, she uses the poetic function of parataxis, to create equality between “Christians, Negroes.” Parataxis makes two things appear to be equals, or parallel, by arranging the words or phrases next to one another without imposing any order or hierarchy between them. Indeed, in this case, one comes after the other with only a comma to separate them. Radical that.

The 7th line is also a direct address to the reader, and it is an imperative sentence, a censure from an 16-year-old enslaved girl. She is calling her readers to account. Saying REMEMBER, Christians: you “brought her” to America (aka kidnapped her) for profit. You told her she was sinful, diabolical. You gave her labels like Pagan and benighted, binaries that she “neither sought nor knew.” And now you’re going to have to share heaven with her.

That is all on the surface of the poem. But there’s more. I came across this reading in a lecture in graduate school and I cannot recover the source, or I’d cite it here (please send me a note if you come across it!):

If you look closely at the subtext of the imagery of the poem, she hints at the Triangle Trade which coupled the commodification of African people with the sugar and indigo trade of the 1770s. Cain, when read aloud sounds like “cane.” There are many words for darkness: benighted, sable, diabolic die (dye), culminating in “black as Cain.” The process by which sugarcane becomes white is “to be refined.” Sugar was the symbol of slavery for British abolitionists in the 1770s, who boycotted it in their tea and cakes to show their solidarity with the nascent movement.

James Baldwin and others have long demonstrated that white colonial Christian rhetoric operates in binaries, and assigns whiteness to the divine. The game is rigged.“Black as Cain” neatly summarizes this. She is a captive in an occupied territory. How does she negotiate this treacherous terrain? To be pagan, to be hated, and then redeemed, and then scorned again? She stands confidently in her faith that she can join the angelic train, and claims the moral authority in an octave.

Phillis Wheatley returned from London and was manumitted at 20 years old. She married John Peters, and they had three children who did not survive childhood. In her 1779 proposal for a second book of poems, she would identify herself as “Phillis Peters.” This second book of poems, though advertised to the same publics that once supported her, never saw print and was lost. She died in 1783. Many critics believe that this last book is a lost grail, the missing chapter in Black American Literature. What would the grownup Phillis Peters have written from freedom rather than unfreedom, now an unfettered genius, writing about her experiences in the Revolution, as a grieving mother, as a free woman in early America? Poet Honorée Fanonne Jeffers spent 15 years in the archive writing The Age of Phillis to help us imagine a future in which Phillis Peters was never lost.

10 days ago, the news broke that University of Albany professor Wendy Roberts has just found an unpublished poem by Phillis Wheatley at the Library Company of Philadelphia. I haven’t read it yet, but she says that it is another elegy from her teenage years, copied into a commonplace book. Hope persists that one day, more will be found.