11. What is it that suddenly forbids her and makes her dumb?

Sarah Orne Jewett, "A White Heron" (1886)

Last week: Henry James, Washington Square (1881)

This week: Sarah Orne Jewett, “A White Heron” (1886)

Next week: Jesmyn Ward, Salvage the Bones (2011)

I didn’t read Sarah Orne Jewett (1849-1909) until recently, and I have only just begun to teach her work in recent years, as I diversified my syllabus to include more gay and lesbian authors. I realize now that I thought of her only as a matronly mentor to others,— the favorites, Kate Chopin and Willa Cather — and around her work I perceived a kind of sea-fog, too few cushions, a forbidding and rocky #coastalgrandmother Maine-ness to her writing. This was all false, and perhaps by design. It is possible that you also haven’t read her work, and if so, please take 20 minutes to read the tale, “A White Heron” or the first few chapters of her most famous work, The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896). You might be enchanted too.

Sarah Orne Jewett’s name often heads up the list for American Regionalism, a “local color” style of writing that emerged in the late nineteenth century, to highlight the diverse “regions” of the United States in a period of extreme population growth and industrialization. In 1880, the population living in cities was about 20% of the U.S. national population. By 1920, the population living in cities was about 70% of the US national population — yes, that’s right, a 50% increase in one lifetime. Regionalism is part to the whole writing, periphery signaling to the metropole that “out there” can be found distinctive accents, food ways, folklore, and stories that can transport us back in time. In Regionalism, writers — themselves living in cities, as Jewett lived in Boston — made a radical deep dive into some place small and out of the way, to demonstrate to fellow readers sitting in New York or San Francisco, that the “America” they remember offers, at its periphery, a diverse landscape, places outside of time where city-ways and modern life have not made inroads. Sarah Orne Jewett’s small, special, out-of-the-way place is “Dunnett,” based on her hometown of South Berwick, Maine.

This writing style borders on nostalgia. It can come dangerously close to heartland thinking. But contrary to our expectation, many of the writers who took it up in the nineteenth-century, and on into the twentieth century, focused their efforts on demonstrating that what you think you know about “America” is white colonialist monoculture, shown to be a false and dangerous assumption, and that the pockets of American culture they write about are equally valid and valuable stories of American life.

In Jewett’s stories, we meet women in their 60s, 70s, and 80s, living alone on windswept outer islands or in cabins in the wood, happy and productive, surrounded by wildflowers, ready to dispense wisdom with a dialect, a healing balm without a recipe, and rough bedding in the barn. These are my kind of people, and I am so glad that I found them in my 40s so that my self-expectations can be raised accordingly.

“A White Heron” starts out in a fairy-tale mode, with a little girl walking home through a wood on a June evening. She is trying to get the cow to come along home, but as the slippage in pronouns in the first paragraph demonstrates, this is no ordinary girl and no ordinary cow. Theirs is a companionship.

They were going away from whatever light there was, and striking deep into the woods, but their feet were familiar with the path, and it was no matter whether their eyes could see it or not.

This is the sort of non-binaried thinking that ecofeminist criticism brings to our attention — there is no hierarchy between human/animal or culture/nature here, no lines of demarcation. They are playmates — the cow likes to play hide and seek, and their game is what has them late to dinner. It is subtly done, but we’re already deep in Snow White territory here.

We learn that Sylvia came to the woods to live with her grandmother, Mrs. Tilley, from a “crowded manufacturing town” when she was 8, and from that moment on, she stayed out of doors.

“As for Sylvia herself, it seemed as if she never had been alive at all before she came to live at the farm. She thought often with wistful compassion of a wretched geranium that belonged to a town neighbor… When they reached the door of the lonely house and stopped to unlock it, and the cat came to purr loudly, and rub against them…Sylvia whispered that this was a beautiful place to live in and she never should wish to go home.”

On this evening, a year later, she is out past sundown and starts thinking, out of nowhere, of the “red-faced” boy who used to “chase and frighten her” back home in the city when she was out on the street in the evening — and it makes her hurry just in the memory of it. Just then, a whistle:

Suddenly this little woods girl is horror-stricken to hear a clear whistle not very far away. Not a bird’s whistle, which would have a sort of friendliness, but a boy’s whistle, determined, and somewhat agressive. Sylvia left the cow to whatever sad fate might await her, and stepped discreetly aside into the bushes, but she was just too late. The enemy had discovered her, and called out in a very cheerful and persuasive tone, “Halloa, little girl, how far is it to the road?” and trembling, Sylvia answered almost inaudibly, “A good ways.”

This begins the conflict in the little tale. Here is a college-aged boy with a gun in the woods with her. Her city-smarts have kicked in and, in my first reading — so had mine! He turns out to be a hunter/birdwatcher who has dozens of birds he has shot and stuffed in his apartment. On this occasion he is after a rare white heron that he saw a few miles back, and “two or three other very rare ones I have been hunting for these five years.” He asks her grandmother for dinner and place to sleep while he hunts.

Sylvia knows all about birds and the woods, and following her grandmother’s example, she warms to him. He offers her ten dollars if she can show him the heron’s nest. The next day, she keeps him company as he looks for the rare bird, and begins to fall a little in love with him, to see him with “a loving affection,” to be too shy to speak unasked, to accept the gift of his attention. All is “charming and delightful” but “Sylvia would have liked him vastly better without his gun; she could not understand why he killed the very birds he seemed to like so much.”

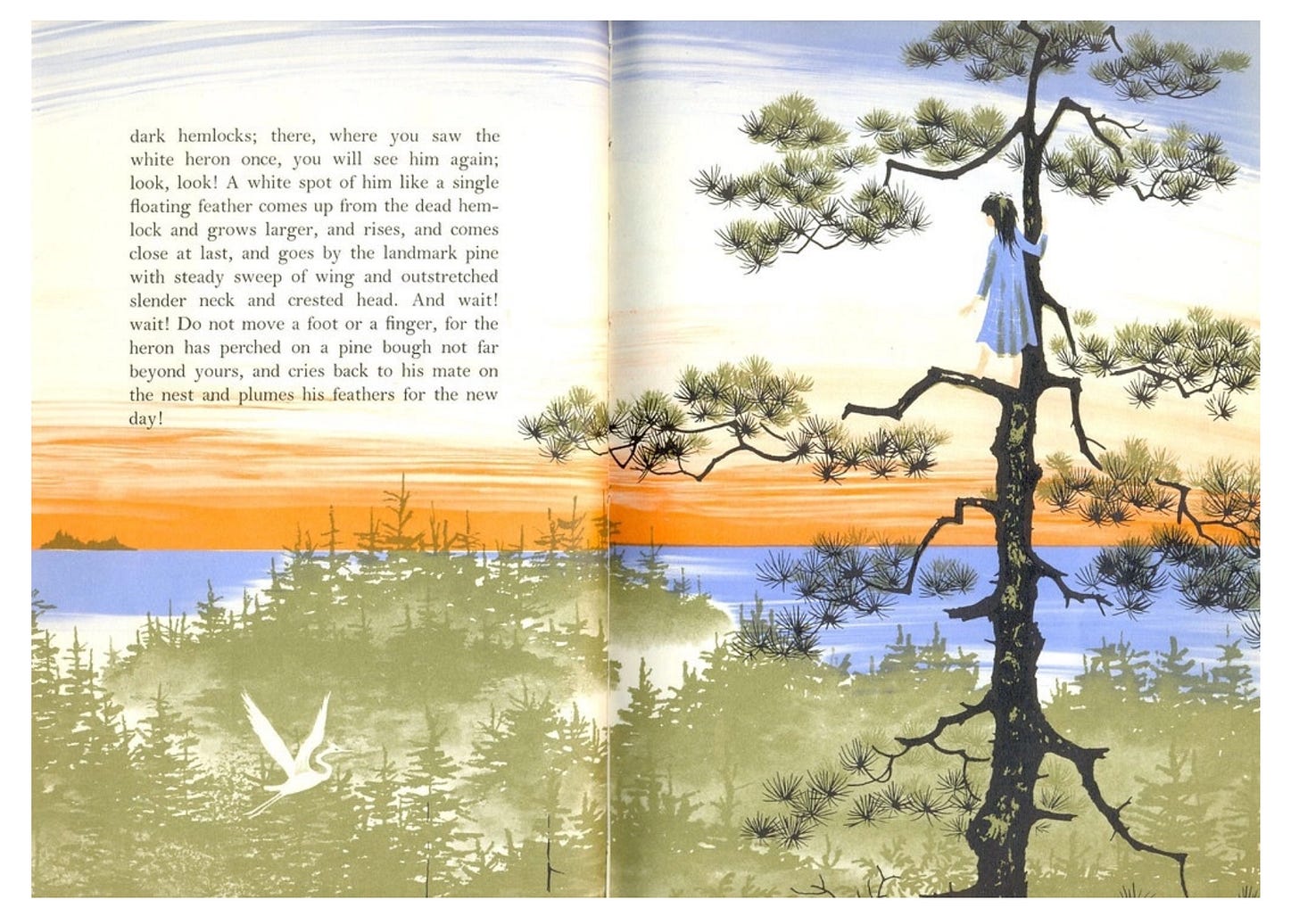

The second night, she decides to climb to the top of a pine tree to see if she can see the bird and give the boy what he wants. She sneaks out once all are asleep to see.

“What a spirit of adventure, what wild ambition! What fancied triumph and delight and glory for the later morning when she could make known the secret! It was almost too real and too great for the childish heart to bear”

She has lived “heart to heart with nature” and this forest is her whole world, and when she sees it from the top of the tall pine tree, her bravery and daring taking her farther than she thought she could go, up the “great mainmast to the voyaging earth,” she is filled with awe. The pine tree holds her steady, with love for the little girl. “Truly it was a vast and awesome world!” she thinks. There among this wonderful sight, is the heron. The child gives a long sigh.

Back home, her absence has been noticed, and her grandmother and the boy stand waiting for her in the doorway together. “The splendid moment” of her glory arrives, and she does not speak.

No, she must keep silence! What is it that suddenly forbids her and makes her dumb? Has she been nine years growing, and now, when the great world for the first time puts out a hand to her, must she thrust it aside for a bird’s sake? The murmur of the pine’s green branches is in her ears, she remembers how the white heron came flying through the golden air and how they watched the sea and the morning together, and Sylvia cannot speak; she cannot tell the heron’s secret and give its life away.

What is wonderful about this ending is that we get to be proud for the girl, who has resisted on behalf of nature, she showed bravery, did not give in to bribery, and remained true to herself, even with ten dollars and admiration hanging in the balance. My students said yesterday that it seemed that so many endings could have happened, but once this one does, it fits so perfectly.

So, it is not a fairy tale after all, and the prince does not rescue the princess. Instead, the princess stays behind, and chooses a different loyalty. The authorial voice sneaks in at a few key moments in this story, and it comes back for a closing, an ambiguous moral.

Dear loyalty, that suffered a sharp pang as the guest went away disappointed later in the day, that could have served and followed him and loved him as a dog loves! Many a night Sylvia heard the echo of his whistle haunting the pasture path as she came home with the loitering cow. She forgot even her sorrow at the sharp report of his gun and the piteous sight of thrushes and sparrows dropping silent to the ground, their songs hushed and their pretty feathers stained and wet with blood. Were the birds better friends than their hunter might have been,—who can tell? Whatever treasures were lost to her, woodlands and summertime, remember! Bring your gifts and graces and tell your secrets to this lonely country child!

We know from this extra-narrative segment that the ending we read so happily was not all that simple or easy for the girl. She has pangs of loneliness and want that stay with her “many a night,” and she’s ready to follow the boy around the woods, “as dog loves.” She forgot all but the best of him. Such a real expression of a girlhood crush!

The narrator admonishes the woods: Quick! step up! give her what she needs!

Can it? Will “the gifts and graces” of the woodlands in summertime be enough to fill the heart of this little eco-warrior? That is the question we are left with, and it’s not clear what the answer should be.