Last week: “Girl” by Jamaica Kincaid (1978)

This week: O Pioneers, by Willa Cather (1913)

Next week: Sin Sui Far, “In the Land of the Free” (1909)

Last spring, I re-read and taught Willa Cather’s O Pioneers (1913). And then, a few weeks later, I picked up Circe (2018) by Madeline Miller at the airport, and devoured it, as you must. Then a few weeks after that, Adrian Van Young recommended Lauren Groff’s The Matrix (2021) to our writing group for its beautiful sentences, and before you know it — I found myself reading the third book in a row by an American woman with the same takeaway: cultivation beats procreation.

Or as my mother and grandmother would say: Bloom where you are planted.

Remember the story by Sarah Orne Jewett, “The White Heron”? (Psst…O Pioneers is dedicated to Jewett) That story also ended with a call for the land to love the girl back, to meet her halfway with a glorious summer after the sacrifice of her crush and ten dollars.

Here are their plot sequences:

A teenaged woman inherits or is exiled to a small plot of land, an island or a wild place, and then slowly comes to understand it, with intimacy and patience, and begins to make something of a utopia out of it. Others are drawn to help her. There is a period of adoration that distracts from the land-love at the center of each of these stories: Alexandra loves Emil and loses him; Circe loves Telemachus and loses him; and so forth. But in the end, it is all about the woman and her land, and her reign as Mother Superior is sovereign and wise. She has cultivated something glorious with her mind. She starts out, alone, in the high winds on a barren plain, and at the end of the novel, she is wrapped in abundance and love.

Do you also see this strange consanguinity?

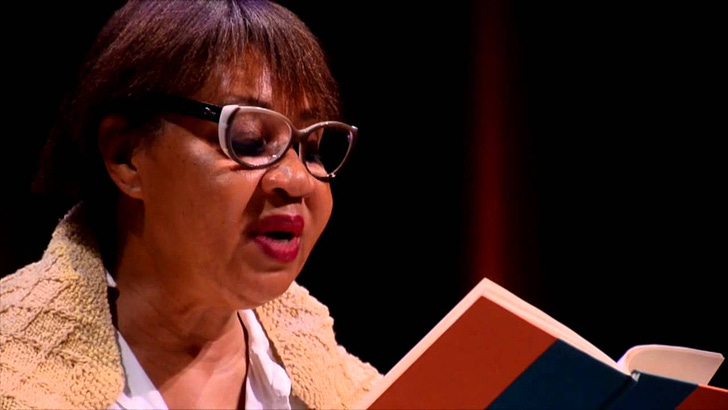

What is this all about, ladies? I asked Lauren Groff when she came to Amsterdam for a reading for a hint. She said something about how our influences are never truly known to us, as they are latent in our minds. So, what are we going to do with this desire to live on a plot of land of our own and cultivate it into our own utopias, an orchard of apricot trees where there was once only bog, for ourselves alone to do magic with?

Also: where do I sign up?

Willa Cather (1873- 1947) was one of these young women once. At the age of nine, her family left Virginia in a hurry — her parents were Union sympathizers, and their barn burned down in 1883. By April, they were in Nebraska — three generations, plenty of siblings, but nothing but prairie and Cathers as far as the eye could see.

I have seen this quote in several places, but I think makes a significant summary of her experience of uprooting and setting out:

We drove out from Red Cloud to my grandfather's homestead one day in April. I was sitting on the hay in the bottom of a Studebaker wagon, holding on to the side of the wagon to steady myself—the roads were most faint trails over the bunch grass in those days. The land was open range and there was almost no fencing. As we drove further and further out into the country, I felt a good deal as if we had come to the end of everything—it was a kind of erasure of personality.

I would not know how much a child's life is bound up in the woods and hills and meadows around it, if I had not been jerked away from all these and thrown out into a country as bare as a piece of sheet iron. I had heard my father say you had to show grit in a new country, and I would have got on pretty well during that ride if it had not been for the larks. Every now and then one flew up and sang a few splendid notes and dropped down into the grass again. That reminded me of something—I don't know what, but my one purpose in life just then was not to cry, and every time they did it, I thought I should go under.

She wrote this around the same time that she published O Pioneers, so you can really see where Cather’s mind was at, as she looked out at this project, this sheet iron that was supposed to be called home. She was sitting in New York City, letting her mind wander over the landscape of her childhood.

Later in life, she would celebrate the prairie, and how the Homestead Act brought peoples from all over to settle there, and how diverse and nourishing it was to grow up in her little town of Red Cloud. And she would make three great novels (out of 12) about women living there, at the “end of everything,” at the Divide. In the novel she gives this line to her friend Carl, whose days are weighted by his habit of nostalgia,

"Is n't it queer: there are only two or three human stories, and they go on repeating themselves as fiercely as if they had never happened before; like the larks in this country, that have been singing the same five notes over for thousands of years."

New Yorker writer Joan Acocella has pulled together a narrative summary of Willa Cather and her critics, because the rise and fall of her reputation as one of the Great American Writers has everything to do with politics, homophobia, and sexism, and nearly nothing to do with the power of her writing. And there is a hesitation now when celebrating pioneers, not for their hard work and perseverance, but for what the Federal Government did to clear the tribals lands that they came from far away to settle.

But I grew up believing that I came “from pioneer stock” and that meant that I would be strong and resourceful as my ancestors, standing against high wind.

In O Pioneers we meet Alexandra Bergson, who has an eye toward the future. Her father, once a shipbuilder in Sweden, had immigrated out to the Divide eleven years previous, and has only just barely broken even, with all the pain and toil that the land demanded of him.

John Bergson had the Old World belief that land, in itself, is desirable. But this land was an enigma. It was like a horse that no one knows how to break to harness, that runs wild and kicks things to pieces.

“He was tired of making mistakes,” the narrator reports, and John Bergson decided to “leave the tangle” to other hands, namely, his visionary third child, Alexandra.

In so doing, he skips over her two older brothers, who are none too pleased when their father, dying at only the age of 46, tells them to listen to their little sister. In the next chapter, Alexandra takes counsel from “Crazy Ivar” a Norwegian man living on the edge of civilization as a religious hermit, barefoot, and in tune with nature. He’s a truly amazing character, who understands how to care for the land and its ecology, with the humility of a hermit and the wisdom of a much older man. Alexandra takes the radical step of asking for his advice and uses it to build her lands into an earthly paradise.

Her best friend Carl, the neighbor and bestie, lets her down, grows up and then finds his way home and into her heart. Her baby brother, Emil who she adores, goes and gets himself killed. There is a lot of capital D Drama on the plains.

But the image that sticks to me from this novel, is in the first few pages.

“Although it was only four o'clock, the winter day was fading. The road led southwest, toward the streak of pale, watery light that glimmered in the leaden sky. The light fell upon the two sad young faces that were turned mutely toward it: upon the eyes of the girl, who seemed to be looking with such anguished perplexity into the future; upon the sombre eyes of the boy, who seemed already to be looking into the past. The little town behind them had vanished as if it had never been, had fallen behind the swell of the prairie, and the stern frozen country received them into its bosom. The homesteads were few and far apart; here and there a windmill gaunt against the sky, a sod house crouching in a hollow. But the great fact was the land itself, which seemed to overwhelm the little beginnings of human society that struggled in its sombre wastes. It was from facing this vast hardness that the boy's mouth had become so bitter; because he felt that men were too weak to make any mark here, that the land wanted to be let alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar, savage kind of beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness.”