23. I do not mean to have it inferred that I ever go to sea as a passenger.

Herman Melville, Ch. 1 "Loomings" (1851)

Last post:

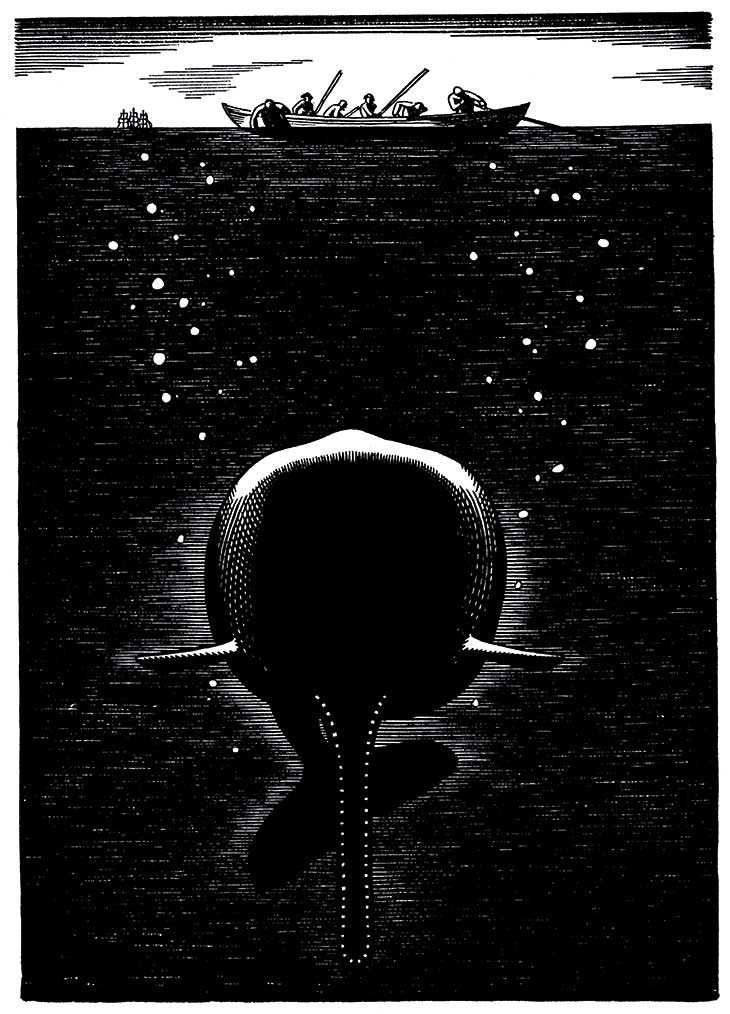

This week I want to talk about one sentence in one chapter of that one wonderfully large and ponderous novel Moby Dick, Or The Whale by Herman Melville (1819-1891). Could I write an entire year of newsletter posts about this novel? Yes. Could I write for several weeks on the first chapter alone? Also, yes. Have I already written essays and lectures on this novel? And yet, yes. Maybe it surprises you how much I love this novel, given there are no women in it and I get seasick. But I discovered narratology and novel theory with this book in 2003, in a graduate seminar with Nancy Ruttenburg, and I never looked ashore again. I remember a professor once said, by way of introduction, that there are two types of people at parties. Those who have read Moby Dick and those who have not. It goes without saying which of these you should strive to become, and which of these fellow sailors you should talk to.

Since graduate school, I have picked it up a few times, and every peek through it makes me feel like a person outside of time. The language in the novel has magic in it. Each chapter is a new experience, a new genre, a new theme. Each line has double, triple, imagined meanings. I am hypnotized by Ishmael and the sub-sub librarian, and with them I look at the world again through whale-colored glasses. It’s hard not to write like Melville once you get deep into the novel, and “the great flood-gates of the wonder-world [are] swung open” again.

Seriously, there is no other writing like it.

If you are yet among the uninitiated, what to do? Reading Moby Dick is a little like embarking on a language course. Do a little every week, and listen to the language often. I recommend the podcast Moby Dick Big Read. (Tilda Swinton reads the first chapter, a delight). It’s easier to hear all the jokes that way.

Get yourself a traveling copy. Don’t splash out for the largish hard-back “This is the Great American Novel” editions.1 You’ll be trapped in an armchair. Go paperback, small, preferably with an introduction and footnotes. Write lots of marginalia. Circle things. This is a talking text, good for long trips, good to read in a group.

And I recommend that you check out the work of Matt Kish for inspiration, as he has painted about every page (all 552) of his copy of Moby Dick:

So, what one sentence do I intend to stand up for our attention?

It’s this one:

Now, when I say that I am in the habit of going to sea whenever I begin to grow hazy about the eyes, and begin to be over conscious of my lungs, I do not mean to have it inferred that I ever go to sea as a passenger.

Twenty years ago, I made a painting at an art party of an airplane, with this sentence in sticky letters across the canvas. At that time, I took this line as a sort of manifesto. I hung the piece in our kitchen. I thought it said something about how I wanted to move through the world, through my life — not as a passenger, but as a person-working, as someone who contributed and pulled my own weight. In my twenties, I wanted nothing more than to be one of the crew.

The phrase “habit of going to sea” refers back to Ismael’s earlier confession, right there in the second sentence of the first paragraph, that he was depressed and perhaps suicidal when he chose to sign up for the voyage of the Pequod. He says has the “habit of going to sea” as a kind of self-care.

Call me Ishmael. Some years ago—never mind how long precisely—having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen and regulating the circulation. Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball. With a philosophical flourish Cato throws himself upon his sword; I quietly take to the ship. There is nothing surprising in this. If they but knew it, almost all men in their degree, some time or other, cherish very nearly the same feelings towards the ocean with me.2

“Call me Ishmael” is the quintessential first line. It packs unknowing and familiarity; the ancient and contemporary; the East and the West; introduction and deception — all into thirteen letters. The first paragraph tells us, in the funniest way possible, that this narrator is going to be just short of impossible, and that he is suicidal.

What is wild, when I read this with students, is how seriously they begin to read this Great American Novel, and how quickly the narrator mocks us and makes us his own. Of course, we “cherish the nearly the same feelings.” Of course “there is nothing surprising in this.”

He says, with some familiarity, that we all (well, all men — it must be said here that he wouldn’t include me in this) cherish the same feelings toward the ocean. Do we all share a feeling that the ocean is better than therapy? I read this “shared feeling” as the desire to step off known land, to drop past the horizon of our lives, and float into the unknown for a few months. The ocean signifies this kind of escape for us, because we don’t know what it holds.

In this week of news of wealthy men lost in submarines, and migrant families lost at sea, and Orcas fighting yachts — the sea still reads as a place of escape, unforgiving strangeness, and fearsome power.

Back to the quote at hand.

“whenever I begin to grow hazy about the eyes, and begin to be over conscious of my lungs”

There is so much truth about adulthood in this brief phrase. When I was in my 20s, I cut the part about the lungs. It didn’t fit on the canvas. But now I know better. There are seasons of life when it is hard to breathe. There are moments when you have to count backwards from 10, while breathing. There are days when a deep intake of air at the seaside or in the forest is exactly what you need, and somehow those days are always spent indoors. And there are weeks when it is hard to focus the eyes or mind on anything.

And so, we must take to the sea. Not as escapism, really, but as a form of survival.

But wait, he writes, he doesn’t want us to infer that when this happens, we should “go to sea as a passenger.” No, the work of life continues. This is not going to be a Four Seasons Maldives experience. Not a pleasure cruise. “Passengers” have money, get seasick and insomnia, are quarrelsome and demanding. We are going to work to save our own lives.

The three paragraphs that follow expound upon this idea. Ishmael, he claims, always goes to sea as a simple sailor. As a sailor, you get paid, which is nice, and you get the freshest air first.

No, when I go to sea, I go as a simple sailor, right before the mast, plumb down into the forecastle, aloft there to the royal mast-head. True, they rather order me about some, and make me jump from spar to spar, like a grasshopper in a May meadow. And at first, this sort of thing is unpleasant enough. It touches one’s sense of honor, particularly if you come of an old established family in the land, the Van Rensselaers, or Randolphs, or Hardicanutes. And more than all, if just previous to putting your hand into the tar-pot, you have been lording it as a country schoolmaster, making the tallest boys stand in awe of you. The transition is a keen one, I assure you, from a schoolmaster to a sailor, and requires a strong decoction of Seneca and the Stoics to enable you to grin and bear it. But even this wears off in time.

When you make your escape from your life, where perhaps you have authority and self-autonomy, to being one of the crew, the transition is the hard part. He says, you must “grin and bear it.”

So, I am in awe of this line, which has this moral imbedded in it. When we go to sea, go not as a passenger, but as a sailor. Leave pride and authority at the shore. This transition, from a schoolmaster to a sailor, is perhaps the necessary first step to clearing the haze and plumbing the depths. Who knows what is out there.

That is, unless you happen to land the 1991 Library of America edition with the introduction by Edward Said, in that case — go for it.

That’s it! You’ve started reading Moby Dick! you might as well keep going. :)