24. We need the storm, the whirlwind, the earthquake.

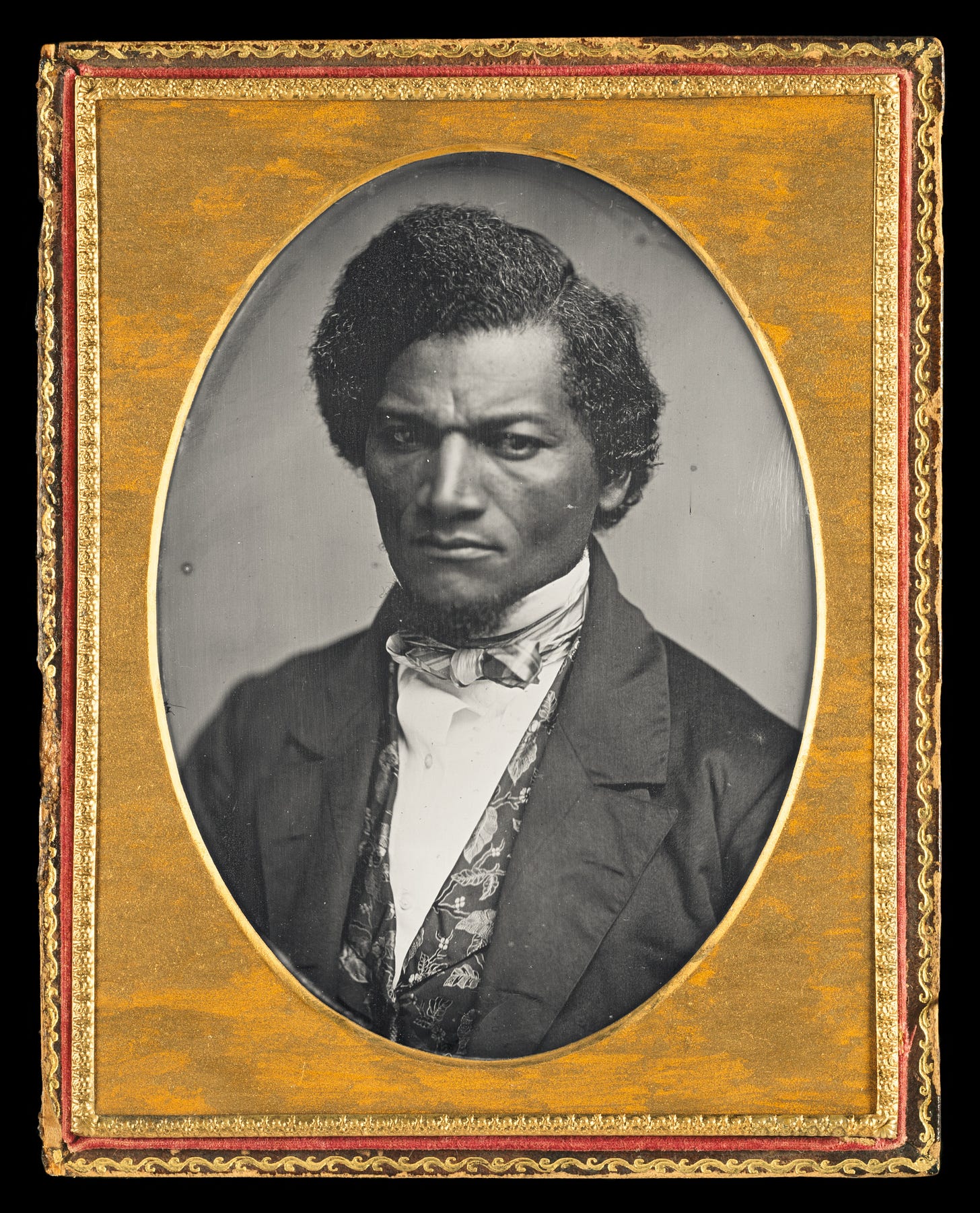

Frederick Douglass, "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?"(1852)

Last week:

This week: Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

When the 34-year old Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) was invited by the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester, New York to give a speech at their July 4th celebration and rally in 1852, he offered a different date: July 5th.

New York State opted for a gradual emancipation of their enslaved population, beginning July 1799 and ending on July 4, 1827. On Emancipation Day about 4,600, or 11% of the black population living in New York at that time were freed. Among them was Sojourner Truth (we’ll come back to her later on!). The day that was commemorated by the Black community was July 5, or the day everyone was freed, so it makes sense for Douglass, who settled in New York, to opt to celebrate then.

I have had the pleasure of reading many of Douglass’s speeches in my research, and many of them are available online in manuscript at the Library of Congress. This speech starts out the same as most of his, with apologies for his ill preparedness (false), and nerves (maybe? likely false), and gratitude for the invitation. I say false, because Douglass was on the lecture circuit 6 months of the year at this time. While his friend, Julia Griffith, the Treasurer of the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society in Rochester finished doing a little fundraising around the room, he spoke of how “brave” the founding fathers were, to secure “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” How great it was to be a part of a “young nation” only 76 years old. He notes how inspiring it is to be so close to those who threw off the oppressive governments of the past. For three pages he recites the story of 1776.

Then, according to the lore, toward the end of the flattery in this soft start to the speech, Douglass gestured for his team to head to the back of Corinthian Hall, and block the exits. It was summer, and it was hot when he started in on these Rochester Ladies.

Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day?

If you look at the full transcript, you can see the turn on page 6, about a third of the way into the speech with this line. I imagine his volume increased in the next segment:

Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?

And he made the celebration that the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society held at Corinthia Hall in Rochester, New York on July 4th an antiracism seminar. In one of my favorite of his speeches, “Pictures & Progress” (1861) he gives this mission statement:

Poets, prophets, and reformers are all picture-makers—and this ability is the secret of their power and of their achievements. They see what aught to be by the reflection of what is, and endeavor to remove the contradiction.

Most of the 600 people now trapped in the audience at the Corinthian Hall would have devoured Uncle Tom’s Cabin that spring. Many of these people were known to Douglass and had seen him speak before. They were allies of the cause, abolitionists, supporters, subscribers to his newspaper, antislavery voters, and friends. And in this long celebrated speech, Douglass “calls them in,” as we would say today. He walks these white allies through their hypocrisy and addresses their misstep in assuming that he shared their holiday. The “secret of his power” as a “poet, prophet, and reformer” is to show them the contradiction between what is and what ought to be, when it comes to the idea of America.

These “calling in” sections are the parts that are most commonly performed and read, and they are words of fire. Check out this reading:

These young Douglass descendants explain how hard it is to keep fighting, to stay focused on the prize of freedom, now many generations hence. As Douglass says, the suffering as always with him, even in the joyful days. He can never forget.

To forget [the enslaved], to pass lightly over their wrongs, and to chime in with the popular theme, would be treason most scandalous and shocking, and would make me a reproach before God and the world. My subject, then, fellow-citizens, is American slavery. I shall see this day and its popular characteristics from the slave's point of view. Standing there identified with the American bondman, making his wrongs mine, I do not hesitate to declare, with all my soul, that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th of July! Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future. Standing with God and the crushed and bleeding slave on this occasion, I will, in the name of humanity which is outraged, in the name of liberty which is fettered, in the name of the constitution and the Bible which are disregarded and trampled upon, dare to call in question and to denounce, with all the emphasis I can command, everything that serves to perpetuate slavery-the great sin and shame of America!

At the halfway point in the speech, he takes up all the detractors that are whispering around the room. Why use rebuke? Why not just explain it one more time to us, what it means to be a slave? To this he announces, that the time for argument is past.

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could reach the nation's ear, I would, today, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

According to biographer David Blight, every year, on July 5th, Douglass would give an updated version of this speech, with Independence Day as his hook and that year’s injustices as its theme. And every year to this one, actors, school children, and news programs recite Douglass’s words. It is a theme that does not tire: Independence Day makes us a promise that is not yet fully realized.

It’s been another quarter of Selected Reading! I will be taking a few weeks to recharge, as I did at the end of last quarter. We’ll be back with our next post soon.

And a reminder, Select Reading is a *free* weekly publication. To receive new posts in your inbox, consider becoming a free subscriber. You can also support this work with a paid subscription, if you want to leave a tip.