His appetite for the marvellous, and his powers of digesting it, were equally extraordinary

"The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" Washington Irving

Last post:

Thanks for the unscheduled break last week! I found myself surprised by a cozy rainy, home day with kiddo. As our first named storm outside, “Ciaran” blew leaves around, I was busy reviewing my notes on Sleepy Hollow. We are deep in pumpkin spice, Hudson valley leaf-peeping season now, so with no further ado — let’s add our friend Ichabod to our growing list of Unforgettable American Characters.

He was tall, but exceedingly lank, with narrow shoulders, long arms and legs, hands that dangled a mile out of his sleeves, feet that might have served for shovels, and his whole frame most loosely hung together. His head was small, and flat at top, with huge ears, large green glassy eyes, and a long snipe nose, so that it looked like a weather-cock perched upon his spindle neck to tell which way the wind blew. To see him striding along the profile of a hill on a windy day, with his clothes bagging and fluttering about him, one might have mistaken him for the genius of famine descending upon the earth, or some scarecrow eloped from a cornfield.

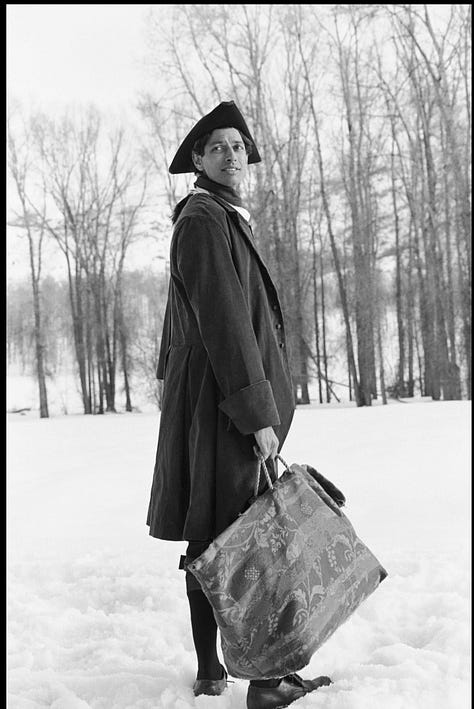

Below the evolution of Ichabod Crane:

This character is one of the most indelible of our canon. And, although the story reads like a folktale, it is entirely made up by one Washington Irving (1783-1859), for The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., which was serialized between 1819 and 1820. “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” was published as part of The Sketch Book in March 1820, and he introduced Ichabod Crane, Sleepy Hollow, and the Headless Horseman into American culture.

Ichabod is a funny looking fellow, a hard schoolmaster, fast with the discipline, into food and drink and in search of a fortune. But more than all that, he is fond of spooky stories. In his spare sack of possessions that he brought to the post in Sleepy Hollow was

Cotton Mather’s “History of New England Witchcraft,” in which, by the way, he most firmly and potently believed. He was, in fact, an odd mixture of small shrewdness and simple credulity. His appetite for the marvellous, and his powers of digesting it, were equally extraordinary; and both had been increased by his residence in this spell-bound region. No tale was too gross or monstrous for his capacious swallow.

The story explains that he would sit in a meadow reading about witches until the light was too dim to read by, and then give himself the delicious pleasure of walking home scared — through the woods and swampy areas of the valley, while

every sound of nature, at that witching hour, fluttered his excited imagination,

A firefly seems brightened by magic forces in his mind, the cattails knocking together are the sound of horse hooves. This is the best part of the Disney version (1949), don’t you think? He would freak himself out so much he had to sing and hurry his way through the dark places. He believes the stories enough to make him scared, but not enough to keep him home, or keep him from reading them.

Another of his sources of fearful pleasure was to pass long winter evenings with the old Dutch wives, as they sat spinning by the fire, with a row of apples roasting and spluttering along the hearth, and listen to their marvellous tales of ghosts and goblins, and haunted fields, and haunted brooks, and haunted bridges, and haunted houses, and particularly of the headless horseman, or Galloping Hessian of the Hollow, as they sometimes called him

But if there was a pleasure in all this, while snugly cuddling in the chimney corner of a chamber that was all of a ruddy glow from the crackling wood fire, and where, of course, no spectre dared to show its face, it was dearly purchased by the terrors of his subsequent walk homewards

So, to begin with, this story is a story about storytelling, about the power of the words and good storytelling to change a quiet walk into the gorgeous Hudson Valley woods into “terrors.”

Washington Irving published the Sketchbook at the very beginning of a new and, for Irving, lucrative genre: the American Short Story. I wrote more about that for our entry on Poe (see here) The short story is thought to have originated in Germany during the Romantic period, as a reworking of the sketch and folktale for the printing press. Irving’s “Sleepy Hollow” is the American magazine and newspaper market version of the German folktale, with extra long sketches followed by heart stopping action. In the short story, Irving introduces the “old Dutch wives” who tell folktales, so that we recognize the lineage.

Local tales and superstitions thrive best in these sheltered, long settled retreats; but are trampled under foot, by the shifting throng that forms the population of most of our country places. Besides, there is no encouragement for ghosts in most of our villages, for they have scarce had time to finish their first nap, and turn themselves in their graves, before their surviving friends have traveled away from the neighborhood, so that when they turn out of a night to walk the rounds, they have no acquaintance left to call upon. This is perhaps the reason why we so seldom hear of ghosts except in our long-established Dutch communities.

“Sleepy Hollow” is as close to an American Folktale as you can come (if you don’t count the Declaration of Independence.)

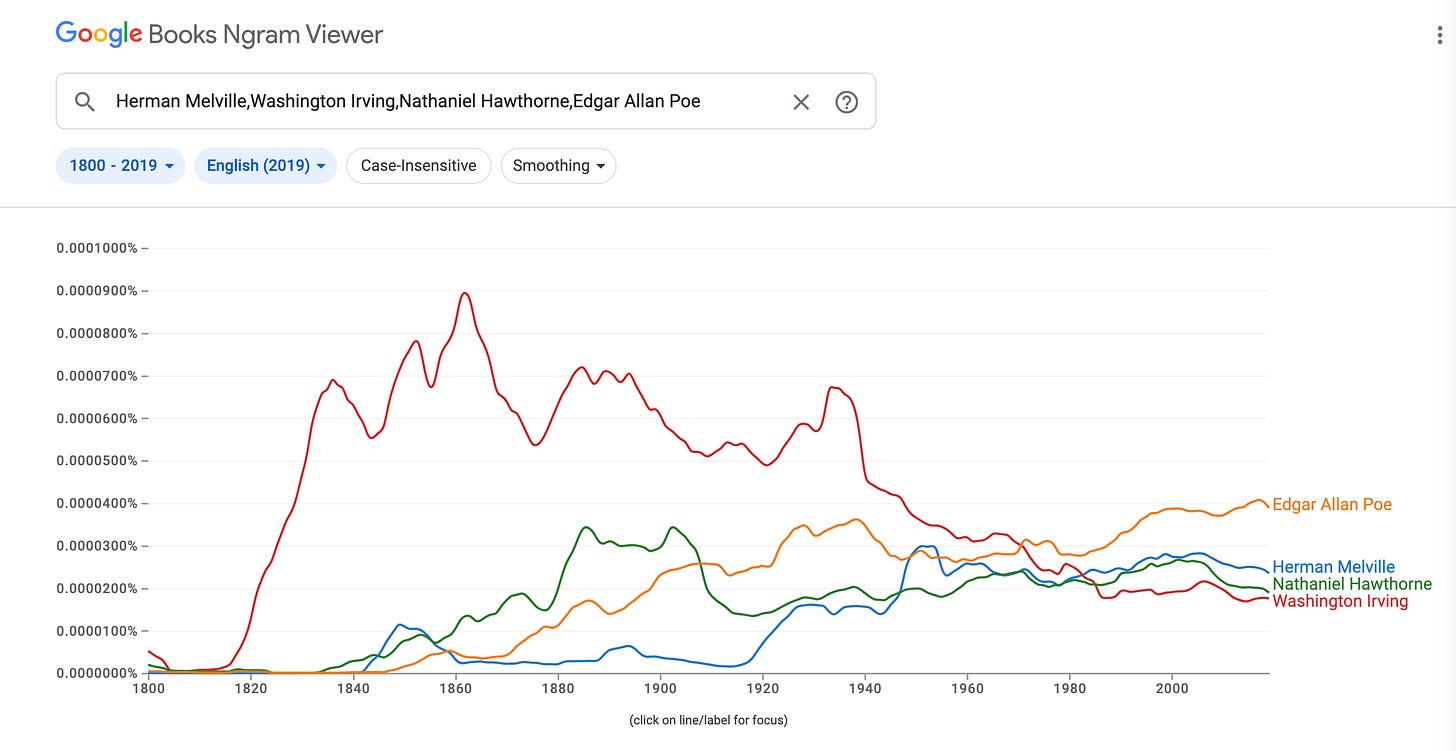

In his lifetime, Irving was a superstar. Over at Google, they gave us the Ngram Viewer, which looks for mentions of a word or name in the entire catalogue of periodicals and books included in their database. Check out the relative popularity, or mentions, or Washington Irving, then and now:

He is credited with challenging the lackluster copyright laws in the United States, making it possible for American authors to compete with European writers in the US, by combating piracy. I was taught that Irving was the “first professional American author.” Today, most of may students and friends have not even heard of him, let alone read him. But they ALL have heard of Ichabod Crane, Sleepy Hollow, and the Headless Horseman (and Rip Van Winkle, his other unforgettable character).

A reminder of the power of stories, and the ridiculousness of canonicity.

At the end of the story, it is unclear whether this happened:

Or Ichabod’s imagination got the better of him. Or his romantic rival Brom Bones pranked him in a costume. Or if you are Tim Burton…the gates of hell opened. Irving leaves the encounter with the ghost inconclusive:

Just then he saw the goblin rising in his stirrups, and in the very act of hurling his head at him. Ichabod endeavored to dodge the horrible missile, but too late. It encountered his cranium with a tremendous crash,—he was tumbled headlong into the dust, and Gunpowder, the black steed, and the goblin rider, passed by like a whirlwind.

The narration shifts at the long dash in the sentence above. From the beginning of the story we were with Ichabod — seeing the world as he does. We were told to watch out for this credulity and imagination, primed as it was by witches and goblins. And here, he encounters a “goblin” and loses consciousness — and after the dash we don’t hear from him again. It’s not a scary story, really — more of a spooky one. The main character disappears.

From here on out, we hear from the community. The Dutch community in the story is described as ancient and set in its ways. Irving celebrates their almost 200 hundred years of prosperous, insulated settlement. They seem to live in a day dream of pastoral abundance and community at Sleepy Hollow. And they happily move on from that silly schoolteacher.

When Ichabod doesn’t show up to the school the next day, a search party is formed and they find nothing but his hat, a smashed pumpkin, and horse hooves. He’s just been paid, the story also mentioned. So his landlord burns his books about witches and calls it even. A new schoolmaster is hired, and the town moves on.

But not the Dutch women, who make his story an indelible part of their fireside storytelling. If you are ever in the Hudson Valley, check out what this story has made in Sleepy Hollow today.

The old country wives, however, who are the best judges of these matters, maintain to this day that Ichabod was spirited away by supernatural means; and it is a favorite story often told about the neighborhood round the winter evening fire. The bridge became more than ever an object of superstitious awe; and that may be the reason why the road has been altered of late years, so as to approach the church by the border of the millpond. The schoolhouse being deserted soon fell to decay, and was reported to be haunted by the ghost of the unfortunate pedagogue and the plowboy, loitering homeward of a still summer evening, has often fancied his voice at a distance, chanting a melancholy psalm tune among the tranquil solitudes of Sleepy Hollow.

Irving gives us another twist to the tale, with a postscript that suggests that Ichabod went to New York and became a successful government worker, but I will leave that for you to noodle on.

If you are into really scary stories, check out my friend Adrian Van Young’s newest collection of frightful tales, Midnight Self — out last month.