Nothing is left but to make the best of a bad bargain.

Jacob Riis, How The Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York (1890)

Today’s text is an early work of photojournalism, rather than literature. A key text in American social history, How The Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York used the new technology of the magnesium flash powder to illuminate the living conditions of New York City’s poor and immigrant communities in the 1890s. Jacob Riis (1849-1914) immigrated from Denmark to New York’s Lower East Side in 1870 at the age of 21 with $40 and a gold watch. He found work as a reporter, and taught himself photography, at first just to make notes for his reporting.

When he was a young reporter, himself an immigrant resident of the tenements, he made extra money by stringing up a sheet and showing pictures on it with his magic lantern, a predecessor of the projector. In 1888, he began to systematically photograph the living and working conditions of what he called the “slums” around him. (I would like to point out that the scare quotes are necessary, in part because of the prejudice that Riis brings to the work — every stereotype about Chinese, Italian, and Jewish people are in play here too.) At first Riis showed the images as magic lantern slides, which he narrated to church groups, community organizers, and wealthy patrons. He backed up his material with his access to police records and the Bureau of Vital Statistics.

Riis gave these performances all the time, from 1870 until his death. His slideshows were filled with anecdotes, songs, prayers, statistics, and fundraising appeals. (Stephen Crane reviewed one of Riis’s shows he caught on the Jersey Shore in a local paper.) In these funny and animated lectures, he adopts a tour guide persona, as though he were leading his middle class audience on a tour of Five Points, a place where most New Yorkers had never been.

His “expeditions” became a documentary photography project, which were published first in a popular magazine, Scribners in the Christmas issue of 1889, and then as bestselling book How The Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York in 1890. How the Other Half Lives was one of the earliest books to employ halftone reproduction of photographs successfully.

His justification comes in the first line of the Introduction:

“Long ago it was said that "one half of the world does not know how the other half lives…" It did not know because it did not care. The half that was on top cared little for the struggles, and less for the fate of those who were underneath, so long as it was able to hold them there and keep its own seat. There came a time when the discomfort and crowding below were so great, and the consequent upheavals so violent, that it was no longer an easy thing to do, and then the upper half fell to inquiring what was the matter.

Riis was a devout Christian, and he believed it was important to share the experiences his neighbors in the Lower East Side. But, as he explains, a willful ignorance blinded the rich and well-off from seeing what was going on inside the tenement buildings downtown.

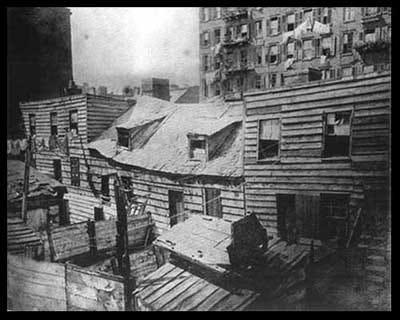

I’ll never forget the time I brought my family to the New York Tenement Museum on Orchard Street, a living history installation, and my mom said, “This looks just like your apartment!” as we entered the first floor apartment. And that is a great description actually — as we would learn, buildings were subdivided to house dozens of families, hidden behind the common facades of New York City. So, while the architectural plans of the brownstones and apartment buildings were the same when they went up, more and more people lived crammed in the tenements than in my little brownstone flat in Carroll Gardens. The definition of a tenement in 1869 was an apartment that house 4 families or more. So, you might walk past a tenement building and not know what was inside its stately facade.

“The worst tenements in New York, as a rule, do not look bad from the outside.”

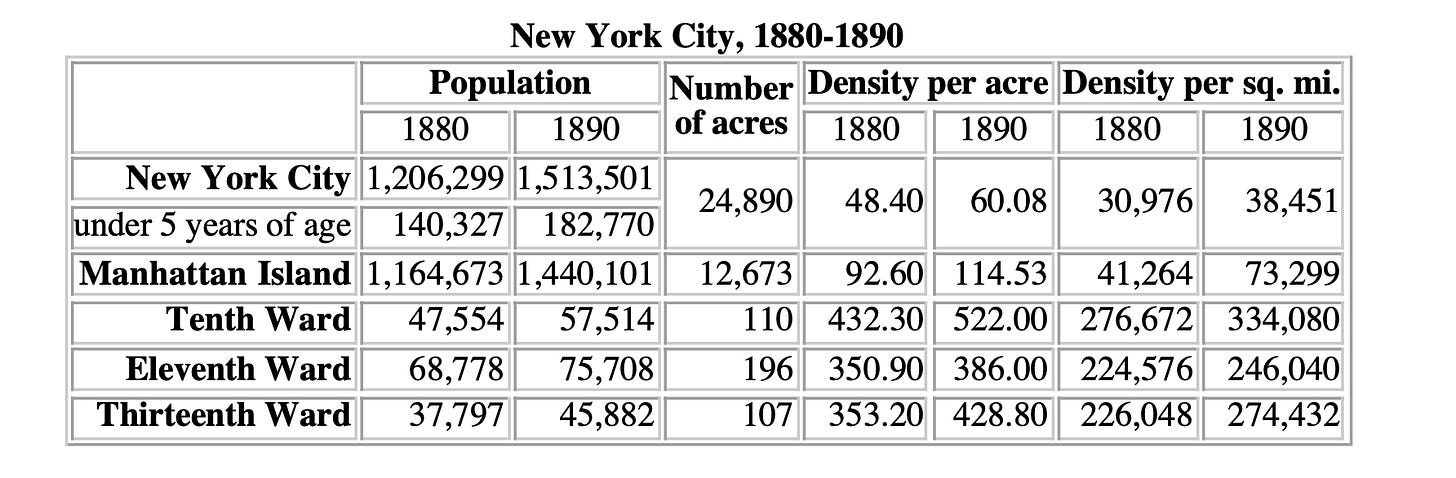

Between 1860 and 1890, tens of thousands of tenement buildings went up around New York (and other U.S. urban areas), and they served as the first landing site of hundreds of thousands of immigrants and migrants to the United States. For reference, Riis provides the following figures:1

In 1889, 349,233 people migrated to New York.

Between 1869-1889, 5,335,396 people were registered in New York’s port of entry.

Number of tenement apartments in New York in 1888 was 32,390. Registered population of these apartments: 1,093,701 people (of which, he points out, 143,243 are children under 5 years of age).

The use of statistics to prove his point stands on the shoulders of Victorian England’s obsessions with documenting and counting the poor. Here, these facts and statistics corroborate opinions that he already has, and his conclusions ring as “self-evident.”

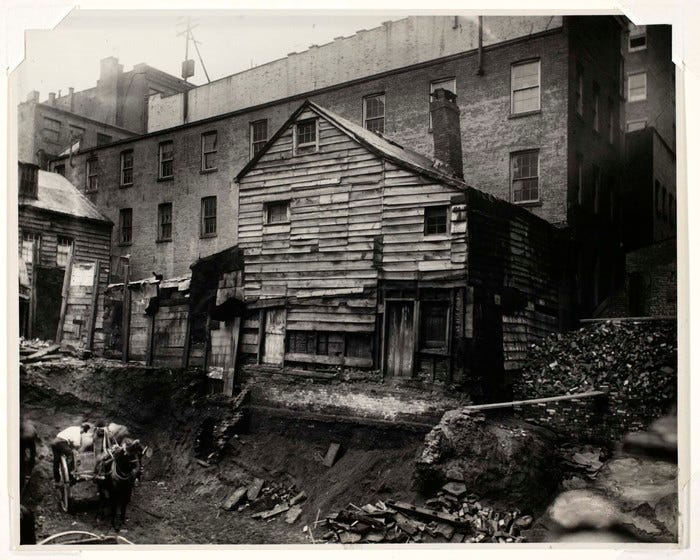

A tenement is a regular apartment that has been divided and subdivided into smaller and smaller residences to be rented out. In some cases the idea of the “residence” is a spot on the floor, a bunk, a place to leave your trunk. Because of the block architecture of New York, there also arose something called the “rear tenement” or an apartment haphazardly constructed in the back courtyards bounded by the buildings that made up the block.

The year that Riis photographed these tenements, the titan of business Andrew Carnegie wrote, in “The Way of Wealth” (1889) that this division of haves and have-nots was not only unavoidable, but essential and even beneficial for humankind:

The price which society pays for the law of competition, like the price it pays for cheap comforts and luxuries, is also great; but the advantages of this law are also greater still, for it is to this law that we owe our wonderful material development, which brings improved conditions in its train. But, whether the law be benign or not, we must say of it, as we say of the change in the conditions of men to which we have referred: It is here; we cannot evade it; no substitutes for it have been found; and while the law may be sometimes hard for the individual, it is best for the race, because it insures the survival of the fittest in every department. We accept and welcome therefore, as conditions to which we must accommodate ourselves, great inequality of environment, the concentration of business, industrial and commercial, in the hands of a few, and the law of competition between these, as being not only beneficial, but essential for the future progress of the race.

Meanwhile, downtown:

As Riis says,

…The boundary line of the Other Half lies through the tenements.

It is ten years and over, now, since that line divided New York’s population evenly. To-day three-fourths of its people live in the tenements, and the nineteenth century drift of the population to the cities is sending ever-increasing multitudes to crowd them. The fifteen thousand tenant houses that were the despair of the sanitarian in the past generation have swelled into thirty-seven thousand, and more than twelve hundred thousand persons call them home. The one way out he saw—rapid transit to the suburbs—has brought no relief. We know now that there is no way out; that the ‘system’ that was the evil offspring of public neglect and private greed has come to stay, a storm-centre forever of our civilization. Nothing is left but to make the best of a bad bargain.

Here we can see two concepts of poverty from the late nineteenth century in conversation with one another. The gazillionaire, Andrew Carnegie, believes that the poor will always be with us because competition is a law of nature. There are winners and losers. While it might be hard “for the individual,” Carnegie writes, poverty is a necessary evil. On the other hand, Riis says, the slums were made by greedy landlords in response to overcrowding. The high death rates to disease, the impossible rents, the working around the clock in low light and without exposure to daylight, alcoholism, depression and despair, sexual assault, and gang violence were all symptoms of these foul living conditions and overcrowding. This was an environmental issue: thousands of ships were landing at Ellis Island, and there were not enough beds for everyone. This situation of the slums was not a consequence of personal failure in the game of life. Greed and forced migration landed these people in a 5-cent bunk in the basement. This was not a moral issue; it was a zoning issue.

The slums were not inevitable. They were built by men and women, and men and women could change them.

The concept behind the term “documentary” to describe photographic images did not exist when Riis started photographing. And further, his reformist intention behind these shots — to changing zoning laws & to make the slums illegal — announce the difference between Riis’s form of “social documentary” and similar photographic projects. Many of his contemporaries saw “the other half,” or the poor of their cities, as Other with a capital O. Riis was not immune to making stereotypical subdivisions about the people he photographed — to be sure there are quite a few stinkers in this books. But he didn’t see the “poor” as a whole separate people.

Over in London and Glasgow, Victorian ethnographers documented the poor of London as if they were in a different, and dangerous, foreign land. In earlier projects that depict the urban poor, the reformist impulse is muted by their more pressing ethnographic impulse. There’s very little sense that their lot could be improved. The “social documentary” — a genre that we now distinguish How the Other Half Lives as inaugurating — combines a commitment to using photograph to show the humanity of the subject, with an evidence that demonstrates a pathway to reform. As Riis wrote:

“words did not make much of an impression—these things rarely do, put in mere words—until my negatives, still dripping from the darkroom, came to reinforce them. From them there was no appeal.”

After seeing How the Other Half Lives in 1895, Theodore Roosevelt, then Police Commissioner of New York, sought out Riis in his newspaper office across from police headquarters on Mulberry Street. Together they made midnight photographic expeditions and became lifelong friends and allies. Roosevelt got the attention of the Board of Health, who shut down 100 cigar making sweatshops, and in 1896, he closed police lodging houses, where people slept on boards on basement floors, and in 1897, he made lights mandatory in tenement buildings, and finally, he made his friend Riis the Secretary of the Advisory Committee on small parks. They got Mulberry Bend, the most notorious slum in the nation, torn down to make room for a city park.

At first, Riis found the rooms were too dark and too close to make legible images. As he recalls in his autobiography, The Making of An American:

One morning, scanning my newspaper at the breakfast table, I put it down with an outcry that startled my wife, sitting opposite. There it was, the thing I had been looking for all those years: a way had been discovered to take pictures by flashlight. The darkest corner might be photographed that way. Within a fortnight a raiding party composed of Dr. Henry G. Piffard and Richard Hue Lawrence, two distinguished amateurs, Dr. Nagel and myself, and sometimes a policeman or two, invaded the East Side by night, bent on bringing in the light where it was so much needed.

He began photographing using the short bursts of light caused by a combination of magnesium and nitrate, which, when ignited, provides a second-long bright white light (and a ton of noise). The resulting images showed the cramped interiors and dangerous living and working conditions of “the other half” of New York at the dawn of the Gilded Age — and the surprised faces of his subjects who have just witnessed a flare go off in their living room.

“It is too much to say that our party carried terror wherever it went. The flashlight of those days was contained in cartridges fired from a revolver. The spectacle of half a dozen strange men invading a house in the midnight hour armed with big pistols which they shot off recklessly was hardly reassuring, however sugary our speech, and it was not to wonder if the tenants bolted through windows and down fire escapes whenever we went.”

For many years, I have taught this photograph of the dozens I could choose from. I don’t know what it is about this one that speaks to me, that makes this one the one that I choose to show and to discuss. The National Archives disseminated a worksheet for reading photography that pairs well with this photograph. To perform the exercise, you split the photograph into quadrants, and make four small lists of the details you spot in each quadrant, and a list of questions that arise as you practice this sustained sort of looking.

This photograph is clearly posed. This family has a gift for self-representation. They are making the best life they can in this place, and even if they were not there you could know something of their character. You can tell that this is their entire home, and that there used to be a window that now opens up into another room. Details and questions, questions and details: the oven door is open. It must be cold in there. There are small napkins decorating the china cabinet shelves. The noise of the flash has made the baby put their hands over their ears. The wall on the right is new. The girls are centered — the second to youngest child in the crib in the center of the frame (is she sick?), and the other in the forefront of the image like a starlet with her Taylor Swift bangs and sateen dress. She is too close to the flash to be recognizable. The eldest boy forever rests his soft, turned hand on the back of her chair.

Thanks for reading! Please subscribe and share.

Obviously, we must take these figures with a grain of salt as the work of a late 19thC activist reporter and his friends at the nascent Bureau of Vital Records. I have not personally substantiated them.