How I feel about The Awakening by Kate Chopin (1850–1904) depends on who I am at the time that I am reading it.

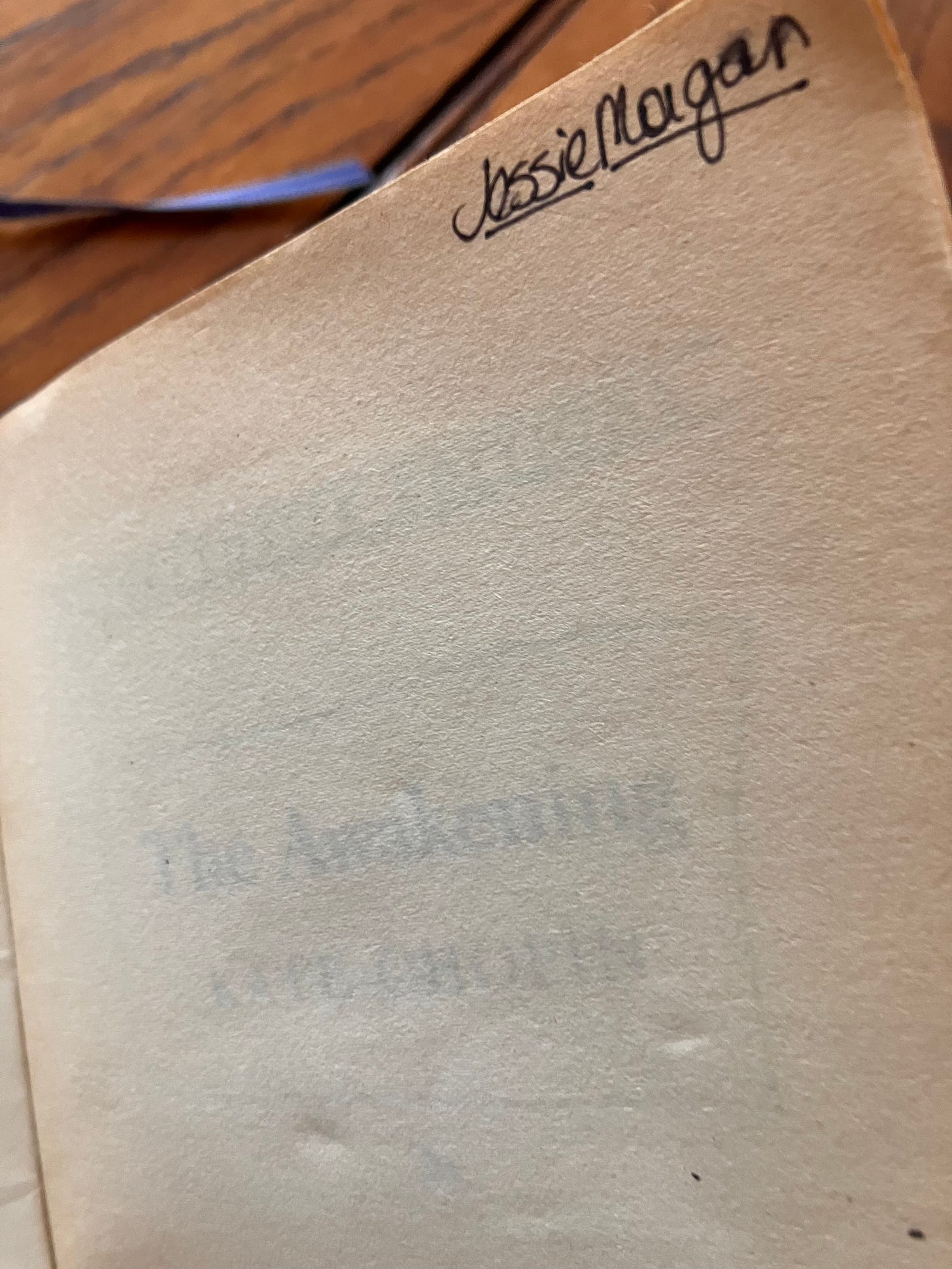

In high school, I was a hopeless romantic, and had already fallen in love with a Creole man when I read this novella about falling in love with a Creole man. I found Edna’s awakening sympathetic, and well, perhaps a little too educational. I learned what happens when you are married and bored, and I learned what happens when you get an apartment on Esplanade Avenue, and what happens when you spend your afternoons painting, or swimming off Grand Isle with someone’s son. I read it hungrily, taking in all the sweet sentences — sensuous ones, sad ones, repetitive ones, and atmospheric ones — and double underlined them with a Bic pen and a big heart. This is the copy I teach from, a sweet visit from that person I was when I was young and knee deep in a love affair so clearly destined for heartbreak.

Then, as fate would have it, this text was the book we got tested on for the AP English exam, a stroke of luck that gave Louisiana students a small, much needed, leg up. Louisiana students in the 1990s read this book for the culture, like we do Ernest Gaines and Walker Percy. I’ll never forget that feeling of collective relief, a big grin across to my friend Talmadge seated catty-corner from me in the cafeteria/gym, after we ripped open the paper seal on the side of the AP test pamphlet and read an essay prompt on The Awakening.

Writing essays on this novel is a no-brainer. For example, you can write about the birds, both symbolic and real, for which there is a bevy of key similes to follow. Or, you can write about the mysterious lovers and the women in black counting beads, who sneak around the edges of every scene set on Grand Isle, always there lurking, but never explained or named. Or you can write about the difference between the “American” Edna and her Creole milieu, whose candidness and physicality are shocking and delightful. Or there’s Edna’s androgyny and its effects on her surroundings to write about. I could go on.

The book structures a college essay on its own in its title. Edna has 5 awakenings in the book, and she stays up all night several times. In these, the awakening is from sleep. For example, when her husband Léonce selfishly wakes her from sleep in chapter 2, because he can, she stays up crying into her peignoir until it is soggy, overcome by

An indescribable oppression, which seemed to generate in some unfamiliar part of her consciousness, filled her whole being with a vague anguish. It was like a shadow,1 like a mist passing across her soul’s summer day. It was strange and unfamiliar; it was a mood. She did not2 sit there inwardly upbraiding her husband, lamenting at Fate, which had directed her footsteps to the earth which they had taken. She was just having a good cry all to herself. The mosquitoes3 made merry over her, biting her firm round arms, and nipping at her bare insteps.

My next favorite awakening is when she awakes on Chênèire Caminada, she finds that she is in love with Robert. She had gone to the island for mass, and feeling faint, Robert finds a hospitable friend to lend her a cool room to rest in. She sleeps the day away, then when she wakes up, she is a free woman.

Madame Antoine had laid some coarse, clean towels upon a chair, and had placed a box of poudre de riz within easy reach. Edna dabbed the powder upon her nose and cheeks as she looked at herself closely in the little distorted mirror which hung on the wall above the basin. Her eyes were bright and wide awake and her face glowed.

When she had completed her toilet she walked into the adjoining room. She was very hungry. No one was there. But there was a cloth spread upon the table that stood against the wall, and a cover was laid for one, with a crusty brown loaf and a bottle of wine beside the plate. Edna bit a piece from the brown loaf, tearing it with her strong, white teeth. She poured some of the wine into the glass and drank it down. Then she went softly out of doors, and plucking an orange from the low-hanging bough of a tree, threw it at Robert, who did not know she was awake and up.4

An illumination broke over his face when he saw her and joined her under the orange tree.5

“How many years have I slept?” she inquired. “The whole island seems changed. A new race of beings must have sprung up, leaving only you and me as past relics. How many ages ago did Madame Antoine and Tonie die? and when did our people from Grand Isle disappear from the earth?”

He familiarly adjusted a ruffle upon her shoulder.

“You have slept precisely one hundred years. I was left here to guard your slumbers; and for one hundred years I have been out under the shed reading a book.6 The only evil I couldn’t prevent was to keep a broiled fowl from drying up.”

This is a gorgeous moment, of a strong woman taking care of herself, of a friendship turning into something more. They sit under the orange trees and listen to Madame Antoine tell pirate stories, and the shadows gather but do not trespass. They take a small boat across the bay homeward, a red sail in the moonlight, surrounded by ghosts.

Robert shares a superstition of a spirit of the Gulf that takes over kindred spirits. Edna is convinced that it is her.

This is the link to the epiphanic awakenings in the novel — when Edna awakens to her body, its handsome strength, or she awakens to the fact that she has never had close friendships when a friend touches her arm without a thought. She reawakens the feeling of childish infatuation when she catches a crush on Robert.

But the other thing that awakens is the beast: existential despair.

I have taught The Awakening a few times in recent years, with a hefty trigger warning for suicide. When I forget to tell the students before the book ends, how it ends, I feel fearful that the surprise will catch them off guard. The book can be morbid, and the deterioration of her mental health feels very real for a lot of readers. Honestly, I don’t know if I will keep teaching it and “The Yellow Wallpaper” and “The Turn of the Screw” — are all the female protagonists going mad in 1900? Students feel this book, and its description of depression so deeply, that it sits on the edge of dangerous.

I reread it as a married mother in my late 30s, depressed and living once again in New Orleans. I admitted over drinks with a friend, that I was jealous of the little apartment Edna finds for herself, without her kids or husband, on Esplanade Avenue, what she calls “the pigeon house.” To which she gave me a side eye and said, “yeah, because that ended well.” Point taken.

Kate Chopin was in her 40s when she began writing. After 10 years of marriage to a Creole man in New Orleans, she found herself with six children, widowed, struggling with her mental health, and buried in debt. Her doctor told her to turn to writing, her hobby of choice, to push back the “shadows” of depression. It turned out that writing solved both problems. Her salacious and sensual writing on Creole society was very lucrative, as were her 27 stories for children. These stories found her a new purpose, on the page.

That said, The Awakening, was a bridge too far. Banned as immoral, and panned by critics, this has only made it more attractive to feminist recovery in the 20th century. And that friends, is how it ended up on my AP English exam.

Rereading as a mother, I felt that Edna’s awakenings to self-awareness are richly described, but she has a striking lack of awareness of her children as individual selves. There is only one scene, right at the height of her unraveling, where she truly allows herself to be their mother and we hear from them. When she does, it is with a touch of mania and it lasts only for one paragraph. The narration shifts entirely to a new register. Exclamation points! Childish gibberish!

How glad she was to see the children! She wept for very pleasure when she felt their little arms clasping her; their hard, ruddy cheeks pressed against her own glowing cheeks. She looked into their faces with hungry eyes that could not be satisfied with looking. And what stories they had to tell their mother! About the pigs, the cows, the mules! About riding to the mill behind Gluglu; fishing back in the lake with their Uncle Jasper; picking pecans with Lidie’s little black brood, and hauling chips in their express wagon. It was a thousand times more fun to haul real chips for old lame Susie’s real fire than to drag painted blocks along the banquette on Esplanade Street!

As she leaves a week later (why does she leave them with her MIL? this is not explained), she allows herself only the space of the journey to be carried away with the feeling of their love, remembering their warm cheeks pressed to hers. But by the time she reaches the city, she has disassociated again, their laughter and music silenced.

“She was again alone.”

As she walks into the sea as her final action, her thoughts go to the children only briefly, to reflect on how they and their father could never “possess her.” She is 29, her husband is 41, and her children are 4 and 5. Girl, wait a minute. Her last narrated thought is a memory of herself as a child:

She looked into the distance, and the old terror flamed up for an instant, then sank again. Edna heard her father’s voice and her sister Margaret’s. She heard the barking of an old dog that was chained to the sycamore tree. The spurs of the cavalry officer clanged as he walked across the porch. There was the hum of bees, and the musky odor of pinks filled the air.

I reread the novel as a New Orleanian after the destruction of Grand Isle in Hurricane Ida 2021, and doing a little research to update my lecture, I discovered a reading by Amanda Lee Castro in her article “Storm Warnings: The Eternally Recurring Apocalypse in Kate Chopin's "The Awakening.” Castro reads the novella as post-apocalyptic.

Yeah, you heard. Post-apocalyptic. Castro makes a contextual reading to show that readers would have had the Hurricane of 1893 front-of-mind when reading this book in 1899. Typically, for naturalist critics, the people are the ones determined and limited by biology and natural forces — and not the natural settings, which are usually figured as timeless, dangerous, and outside human control. Further, Grand Isle and the Chênèire Caminada are figured as utopia, even pre-fall Edens, where Edna can learn to swim and find herself, romantically and sexually. As Castro points out, this is a long standing trope, locus amoenus, or pleasant, ideal place from Homer and Virgil, outside the wilds of Nature with a capital N. Chopin opens her novel with her heroine ensconced in an ideal and restful place that promises her safety, but this utopia every contemporary reader would have known, was about to be obliterated and rendered unsafe. This future for Grand Isle underscores the hopelessness of Edna’s project of finding herself an ideal home and restful heart. Here’s Castro:

A similar disparity existed in the minds of Chopin's contemporary readers, who remembered the islands as both the resort culture Utopias that they used to be and as the sites of natural disaster that they had become, and the coexistence of Utopia and dystopia in the novel's island setting mirrors this same dissonant collective memory.

This puts the passage under the orange trees into a different perspective, one where the shadows fall. I remind you that Edna says,

“How many years have I slept?” she inquired. “The whole island seems changed. A new race of beings must have sprung up, leaving only you and me as past relics. How many ages ago did Madame Antoine and Tonie die? and when did our people from Grand Isle disappear from the earth?”

Reading this now, I feel yet a third way about it. Two-thirds of the population of the Chênèire Caminada were lost in the storm of 1893 (is that how Madame dies?) and the threat of storm and sea rise has rendered Grand Isle unrecognizable in my lifetime — let alone in 100 years. Chopin’s novella now has a place on my shelf as a “past relic” of a lost time.

Hello readers! I have not been posting with my usual regularity in 2024. My schedule changed, and with it, my energy to write down these lectures at week’s end. But I asked a few of you readers about this, and you said — “Honey. We are just happy to hear from you when we hear from you.” So, that’s how I’m going to roll for the next little while. See you soon!

Teenage Jessie wrote unoriginally in the margins that Edna is “still in the dark before really awakening—shadow=symbol of oppression”

Don’t read this sentence too quickly — it says she did “not” blame her husband or her situation, but instead the mood is directionless, like depression.

I have only vacationed on Grand Isle for one night and people, let me tell you, the mosquitoes are insane.

Yes, this is giving Eve. We are in a pre-fall Edenic space here.

I’m thinking of the “my husband before he sees me” meme here.

Why not tell us what book? Did he bring it with him? Also, when I read this book the first time, it was 100 years after its publication so my marginalia is psyched.