Public monuments are silent. Their ability to memorialize depends upon the stories we tell of them and the traction of the symbols they employ. Historian James Young wrote, concerning Holocaust memorials, that “Memorials by themselves remain inert and amnesiac, dependent on visitors for whatever memory they finally produce.”1

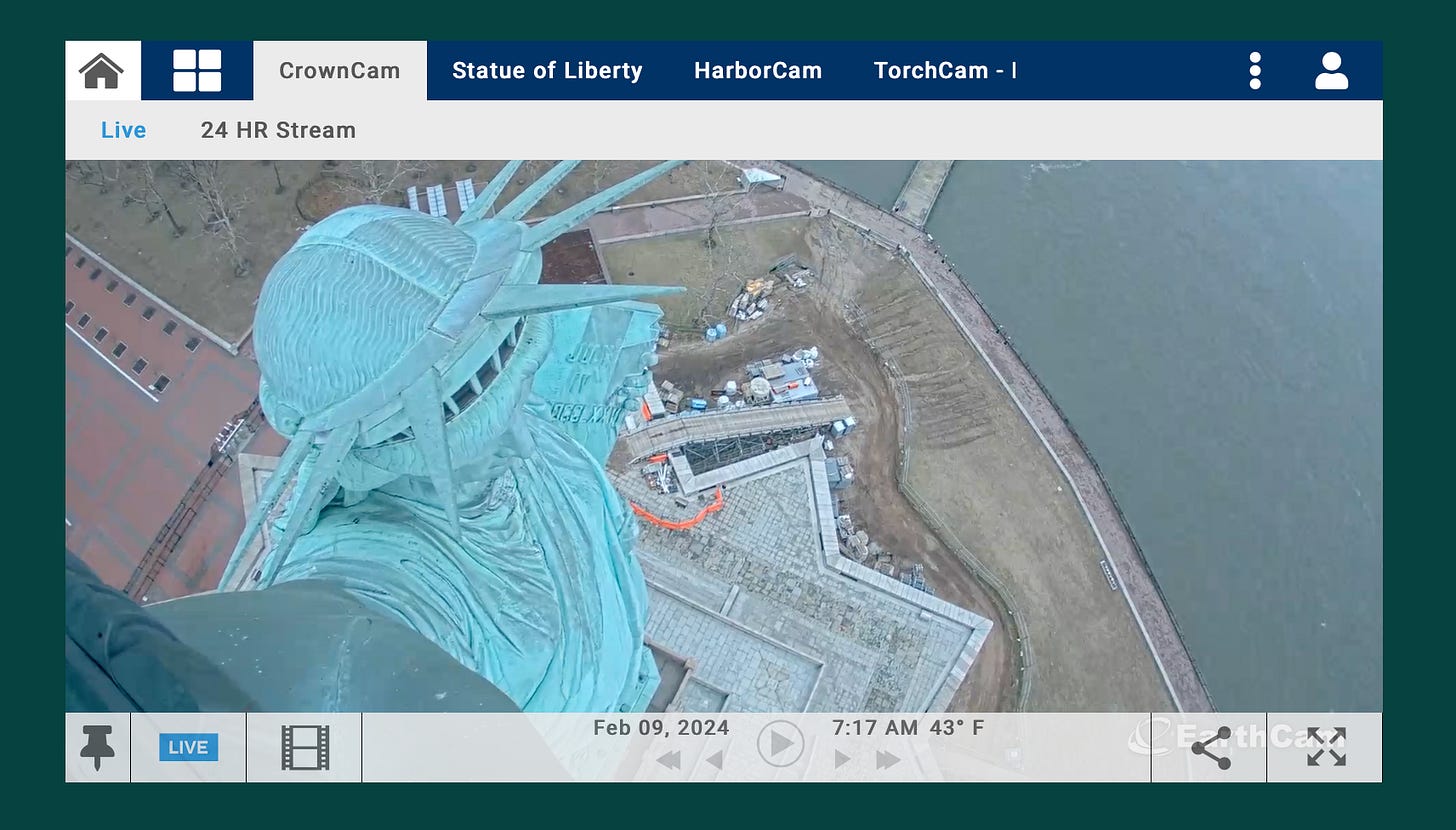

In 1865, the French thinker and anti-slavery activist, Edouard de Laboulaye wished to commemorate the Emancipation Proclamation, Union victory, and the passing of the 13th Amendment. He envisioned a colossal statue to be presented on the centennial of the United States (it was late). The sculptor Auguste Bartholdi chose a hefty symbolic pallet of Roman goddess, broken chains and shackles, a crown of sun rays, the lighted torch, and a tablet with the date July 4, 1776 written across it. He visited New York harbor on a recce trip in 1871, and decided that she would be placed on Bedloe’s Island, since her message would be visible to every ship that entered New York Harbor. He called the statue, “Liberty Enlightening the World.”

Did you know that the statue of liberty also commemorated the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States? No, me neither! While there were a gazillion (or there about) monuments to the Confederate and Union dead erected after the Civil War, there were surprisingly few monuments created to those lost to slavery. Toni Morrison once said, in an interview,

There is no place you or I can go, to think about or not think about, to summon the presences of, or recollect the absences of slaves . . . There is no suitable memorial, or plaque, or wreath, or wall, or park, or skyscraper lobby. There’s no 300-foot tower, there’s no small bench by the road…2

So, it turns out that the 305 foot tall Statue of Liberty was conceived of as a monument to emancipation, but does it do what Morrison asks of it? Are the presences and absences of slaves symbolically indicated in the stamp of her green foot on these chains? It seems to me that this representation of LIBERTY as the Roman goddess Libertas, as a colossus, as a symbol of democracy, gives more weight to those who did the freeing than those whose lives were lost in the effort. Perhaps if she were a Black woman, then we could see this face of the monument more clearly.

The French, through lotteries, taxes, and fundraising, paid for the statue; the United States had only to supply the land and the pedestal. Is it any wonder, then, considering the politics of 1885, that we didn’t have the cash raised yet when Lady Liberty started coming our way, in small pieces?

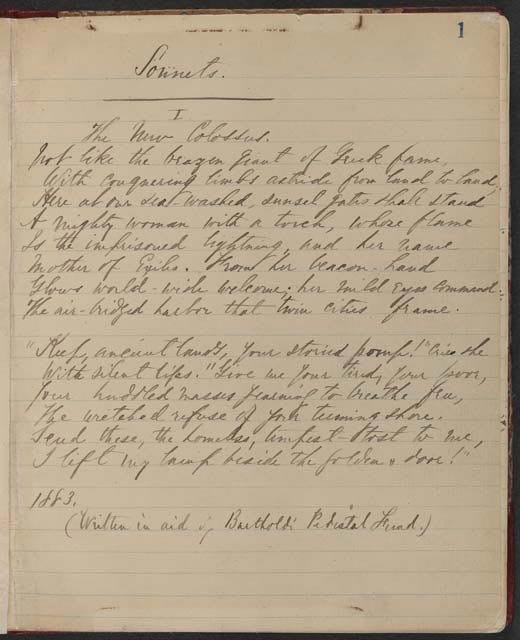

I learned that the Statue of Liberty had this other meaning when I was writing a new lecture this month on Emma Lazarus (1849-1887) and her poem, “The New Colossus.” I wanted to include this poem on our syllabus for the Gilded Age course because I was struck by the tension between the famous last lines of the poem and the near total anonymity of the poet. Have you heard these hopeful lines?

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Do you know another of her poems?

The wealthy and well-educated daughter of Jewish immigrants to New York, Emma Lazarus began publishing poetry at 18, with a collection of her writings composed between the ages of 14 and 17 (!). She released many further successful editions of poems and translations (particularly of the German poet Heinrich Heine), and attracted the attention of the literary elite. In her adulthood, she began to focus her writing and philanthropy on anti-seminitism, the pogroms of Europe, and Jewish refugees living in New York. In short, she became a political poet, and an experimental one at that. “The New Colossus” was among her last publications, and it suggests, as do many poems in her collection Songs of a Semite (1882) that the political futures of the United States and the Jewish people would be intertwined through immigration. One literary critic writes:

Drawing on the biblical tropes of American political rhetoric, she insists that if the United States could be the Promised Land or New Jerusalem of the Puritan imagination, the land to which they came viewing themselves as new Israelites leaving Europe in a modern-day exodus, then it could certainly play that role for the oppressed Jews of 1881.3

So when the fundraising committee came to Lazarus asking for a donation to their arts and literary catalogue, she provided them with “The New Colossus,” which summarizes this view. It was published in their catalogue. Here is the whole thing:

While critics have distinguished Lazarus as an experimental writer, with perhaps holding the title of publishing the “first prose poem in English,” this poem is a very regular sonnet. Ten points if you knew that already!

The rhyme scheme mirrors the content, with ABBA on comparing the Colossus of Rhodes (one of the seven wonders of the ancient world) to the Statue of Liberty, then ABBA on her glowing welcome to exiles; and finally the famous speaking statue lines in couplets, CDCDCD. The rhyme scheme comes straight on and gives us this silly refrain of C-lines: she—free—me

The simile that begins the poem sets up a comparison between the ancients and America, which favors the mighty woman with the torch. But the real rebranding comes in the 6th line:

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.4

And that is how the Statue of Liberty, erected to commemorate domestic emancipation, came to signify international asylum. She becomes a beacon to the ships and ships of immigrants from Europe, as they pass by her on the way to Ellis Island. Nativism and anti-semitism were on the rise, and as immigration became the hot political issue that is still is today, Lazarus wrote this poem in support of those who emigrate to America. It is an ode to pluralism. According to her biographer, Bette Roth Young, the poet James Russell Lowell wrote to Lazarus that “Your sonnet gives its subject a raison d’etre.”5

Lazarus died of cancer in 1887 shortly after returning from a book tour of Europe, (which makes me daydream that she saw the statue on her way into New York harbor). It was her friend Georgina Schuyler (WERK!) that decided that the poem should be mounted at the base of the statue, 12 years later. “The New Colossus” appeared on a plaque on Liberty Island in 1903.

Today, as I write this I think of the stark contrast of her fever dream of liberty and the reality of occupied Palestine, where the refugees are “yearning to breathe free,” in their own land. History knots and binds those who dare write odes or erect monuments to messages they can’t foresee.

See page xiii in James Young, The texture of memory: Holocaust memorials and meaning. Yale University Press, 1994.

From interview with The World, 1989. See http://www.tonimorrisonsociety.org/bench.html for information on the “bench by the road project” that seeks to provide this. More on this when we talk about Beloved in the coming weeks.

Wall, Joshua Logan. "“Talking Hebrew in every language under the sun”: Emma Lazarus, Charles Reznikoff, and the Origins of Documentary Poetics." Modernism/modernity, vol. 27 no. 1, 2020, p. 27-49. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2020.0001.

Important to note here: Lazarus was also a Zionist.

Back then Brooklyn was its own city.

Check out Poetry Foundation’s blog for more backstory: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/144956/emma-lazarus-the-new-colossus

About the subscription: This newsletter is 100% free. Feel free to subscribe without paying. The paid subscription option supports the work financially. I also love the support you give by seeing your likes and hearing from you directly in the chat. Both subscription options offer the exact same content, except that my paid subscribers — hi Mom! — can comment.