Last week:

This week:

Clint Smith, “August 1619” for “A New Literary Timeline,” New York Times Magazine issue “The 1619 Project” (2019)

For the last three weeks, we have been discussing the problem of origins in American literary history. Where do we begin? Which landing do we turn to and how does that story go? We looked at the Iroquois Creation Story as recorded in 1827, we survived Spanish colonialism with Cabeza de Vaca, and we rode along with Anne Bradstreet and John Winthrop’s spiritual and social transformations.

In January 2019, then staff writer for The New York Times Magazine Nikole Hannah-Jones pitched a special issue commemorating the 400th anniversary of race-based chattel slavery in what would become the United States. The project put forward a bold new point of origin: when the Dutch ship The White Lion arrived at Point Comfort Virginia in August 1619, and traded 20-30 African people for provisions. These were the first enslaved Africans in what would become the United States. Forget the Mayflower, the editors argued, is when/where American culture truly began.

The special issue of the magazine, then podcast, book, and web series centered ideas that were all hotly debated in the United States: that the story of the United States is inextricably tied to the history of enslavement, and that gains made through African American struggle and activism have perfected American democracy and liberty. The essays, poems, and illustrations registered the sheer weight of slavery’s importance in the foundation of the United States (politically, economically, socially, you name it). There was widespread acclaim and unprecedented vitriol. When Hannah-Jones visited Leiden last year, she described a tsunami of glory and fury from which she is only now beginning to emerge.

The original magazine issue featured 10 essays and 17 original literary works, reflections arranged around a specific date.1 Of the poems, there are two that I teach: “1773” by Eve L. Ewing (which I mentioned in the post about Phillis Wheatley, way back in January —one of the first posts here on Select Reading)— and today I want to talk about the other one, “August 1619” by fellow New Orleanian poet, historian, and educator Clint Smith (1988-). His nonfictional work How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning With the History of Slavery Across America, takes a tour around historical sites in the US, to show how little we learn about the history of slavery, and he has a Crash Course on Black American History on YouTube that tries to correct for all that crapola. He first became known to me as a poet (*and also through his mom, an anesthesiologist, who regularly volunteered at career day at the high school early college I worked at in New Orleans). His poetry is collected in two volumes, Above Ground (2023) addressed to his two young children, and Counting Descent (2016), which talks a lot about ancestors.

If you want an approachable but searing take on history and life as a Black American man, I recommend the whole shelf. The fun of reading a contemporary is that you get to look forward to more.

The poem “August 1619”:

The poem toggles between fact and feeling. We have data stated in an objective factual tone, followed by the physical movements of a persona, the speaker of the poem “I” who “walks,” “drags,” and “slides”… “& feels” this data. The pattern is established in the first of eight 3 line stanzas:

Over the course of 350 years,

36,000 slave ships crossed the Atlantic

Ocean. I walk over to the globe & move

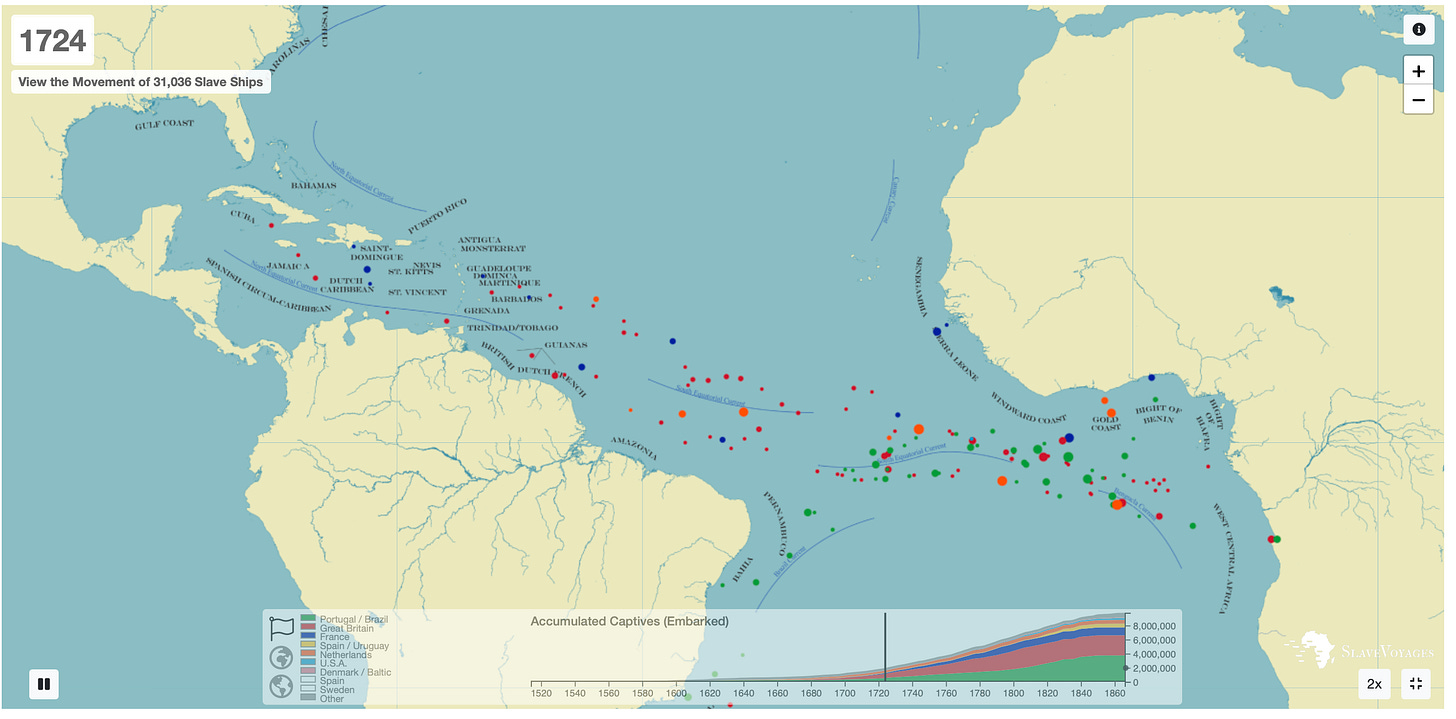

The facts are there even if the history has been purposefully obscured. The data is known because these ships were all insured. You can watch the 36,000 ships criss-cross the Atlantic here in this infographic.

Students notice the historical documentary tone right away. The poem seems to ask, How can I make such big numbers knowable? How do I understand this data, which touches me? One way we make sense of the world is through touch. The poem tries to make sense of the statistics of the middle passage in the body, by attempting to reach out and touch history by hand. “I walk over to the globe” they say, in the present tense. Then the poet physically recreates the movement of 36,000 ships across 350 years with their fingers — the index finger, the thumb, the ring finger. This attention to how it feels to run your fingers over the surface of a textured map gives the poem a tactile layer.

my finger back and forth between

the fragile continents. I try to keep

count how many times I drag

my hand across the bristled

hemispheres, but grow weary of chasing

a history that swallowed me.

The commitment here is to gesture — to acting out the ships’ passage across the ocean by tracing the voyages by finger. Think of it — there are 36,000 gestures embodied here, and the poet “grows weary” before they finish. Even the attempt to make this number knowable by making it tactile is exhausting — we cannot feel this number. It is too many. It overwhelms us.

The poet makes this data personal at the end of the third stanza by including themselves in this history. No longer are we safely in the study, conducting statistics and tracing a globe — we are drowning in history, swallowed up.

Looking back over the first three stanzas we got a few hints of what this poem is capable of. There are these adjectives cropping up. At first they seem descriptive — it is an old globe, the kind with raised terrain— but then, after we hear the powerful line “a history that swallowed me” the surface descriptors take on a more treacherous meaning. “Fragile Continents”; “Bristled Hemispheres”: these metaphors go hard. We are talking about global interactions as a threat.

The second fact takes up all of stanza 4. Our friend anaphora (remember? it’s when the first words repeat in successive clauses or lines, Greek for “carry back”) organizes the following three stanzas — the speaker begins with an action of the hand on the globe:

I pull my index finger from Angola

to Brazil & feel the bodies

jumping from the ship.

I drag my thumb from Ghana

to Jamaica & feel the weight of dysentery

make an anvil of my touch.

I slide my ring finger from Senegal

to South Carolina & feel the ocean

separate a million families.

The poet has trained us to look out for this. In the previous 3 stanzas, Smith gave us a caesura, or punctuation and pause, in the middle of the second line. It’s a sign that we readers are supposed to take a breath. Here, the punctuation is an ampersand, so we must pause and take a breath before the repetition of "…& feel.” He might have put this word in red paint, for all the work it is doing in this poem. The speaker desperately wants to FEEL the middle passage — the weight of it, the pain of the separation, the suicidal desperation.

That is the hurt in the poem, this gulf between the statistics and the reality, the facts and the feeling. The speaker struggles to understand it, to feel it — because it is personal, “chasing/ a history that swallowed me.” For the entire poem, I believe, we are meant to picture the speaker dragging a hand across the globe in pursuit of the 36,000 ships, the millions of families lost.

The last stanza is situated in the tone that would have introduced a new fact. So we should read this statement as factual, as a type of thesis statement:

The soft hum of history spins

on its tilted axis. A cavalcade of ghost ships

wash their hands of all they carried.

This mic drop of an ending gives us two key takeaways: History is skewed, tilted by ideology. The “soft hum” is the background noise of accepted historical narratives. The other key takeaway comes in the second part (see that caesura? dang Clint!) is that the enslavers have evaded culpability. The whiteness of ghost ships is subtle, and even if it is not racial, the last line is clear: there has been a purposeful, formal renunciation of responsibility, as he alludes to Pontius Pilate, washing his hands before saying “I am innocent of the blood of this just person” (Matthew 27:24). The nations and religions who share this culpability for these many deaths have marched the same march, in a tightly knit cavalcade of historical forgetting that has only recently begun to unravel.

Select Reading has a whole lot more to go! Thanks for reading and go ahead and subscribe.

Because of the power and notoriety of the project, Hannah-Jones was able to bring together more essays and literary writing for the book version of The 1619 Project, and many more stars in the field of American history and literature weighed in, among them Claudia Rankine, Matthew Desmond, Michelle Alexander, Martha S. Jones, Ibram X. Kendi, Tiya Miles and Dorothy Roberts. This edition was also peer reviewed, making it invaluable for classroom use. For more on the origin story of the 1619 Project, see this article.